Bad Health Journalism: ultra-processed edition

Ultra-processed foods are the hottest subject in nutrition. Is it too much to ask the journalists writing about them (and the researchers studying them) to think critically?

Housekeeping again: First, for those who prefer brevity, I still hope to keep future posts short, or at least considerably shorter. I am so far failing to do so. Have patience.

Second, in the next month, as I hope to write more frequently (and shorter posts), I’ll start inserting a paywall in some posts to generate income. I’m grateful in advance to all who see my work as worth supporting.

The ultra-processed post-script on bad health journalism.

“Worse than meaningless…”

That’s how the most influential nutritionist of the last thirty years, Walter Willett of Harvard, described the most influential nutrition research article of the last five years. And he did so on the record in a New Yorker article, ostensibly about “Why the American Diet Is So Deadly.”

Does that not make you wonder, what’s going on here?

Is there a problem with the science of nutrition, circa 2025, that we might be missing?

Not according to the New Yorker. The article, published last week, barely touches on the reasons why Willett would make such a brutally dismissive comment about such remarkably influential research. It forgoes entirely any discussion of the broader implications for nutrition research and the public health.

In short, we’re back to bad health journalism.

The subject of the New Yorker article is ultra-processed foods (UPFs), which are, by far, the hottest subject in nutrition science. The topic is so hot that the latest articles have taken to focusing their attention on research that’s yet to be published, with the Wall Street Journal, the Economist, and The New York Times all recently running variations on the same article that the New Yorker published this week.

Here’s the gist of all four, in a nutshell:

Nutritionists may finally have made a breakthrough, identifying ultra-processed foods as the likely explanation for the explosion of obesity and diabetes in America and around the world.

The yet-to-be-published results of a small clinical trial at the National Institutes of Health are the best bet we have to understand why. And the reason we can believe this research will shed the necessary light on this subject is because the principal investigator, Kevin Hall, is the primary author of that remarkably influential 2019 study.1

That this is the same study that Willett dismissed as “worse than meaningless” should suggest the nature of the problem we’re confronting.

In both the New Yorker and New York Times articles, the authors described their visits to Hall’s NIH laboratory so they could understand his latest groundbreaking experiment up close and personal.

It was Hall’s 2019 results that the NYU nutritionist Marion Nestle references last month in the Times, when she suggested that the authors of the next Dietary Guidelines would be making a mistake if they did not counsel Americans to limit their UPF consumption. (“Why the Next Dietary Guidelines Might Not Tackle Ultra-processed Foods,” was the headline of that article.) Hall’s experiment, the Times said, citing Nestle’s expertise, was “tightly controlled and clearly showed that ultra-processed foods cause people to overeat and gain weight.”

Last week’s New Yorker article says much the same: Hall’s study was “the first randomized trial demonstrating that ultra-processed foods disrupt our metabolic health and lead people to overeat. It was hugely influential and is widely recognized as the most rigorous examination of the subject so far.”

So here again is what seems to be an obvious question, the kind I would hope these journalists would clarify for us: If a study that is “hugely influential,” and “widely recognized as the most rigorous examination of the subject so far” is also potentially “worse than meaningless,” doesn’t that suggest something we should know, perhaps vitally important, about all the other less rigorous and influential research in the field, and perhaps about the researchers who are making these decisions about what is rigorous and what should be influential?

To be fair, the New Yorker article acknowledges that the 2019 study “sparked controversy and opposition,” but then it summarizes the nature of the controversy in two sentences (in an article that is 6,800 words long) before moving on:

By necessity, the study was conducted in a highly artificial environment. Some of its findings might not have persisted; in the second week that participants ate an ultra-processed diet, for example, their excess calorie consumption started to fall.

Why these issues might be important to the interpretation of the study is a question that goes unasked and unanswered.

It’s as though the writer stumbled over a landmine that had the potential to blow up his story and its thesis, but he wasn’t going to let that happen. As Churchill might have said, he picks himself up and hurries on and, in doing so, ignores what might been the far more important story, which are the implications to the state of the science in nutrition and obesity.

Here's where I wonder if the authors of these articles even understand the nature of scientific progress. Or if they do understand, do they care if their readers do? Maybe they don’t see that as part of the job.

“Controversy and opposition,” for instance, are what every new and seemingly remarkable finding should confront in science. This resistance, knee-jerk as it can seem, emerges from the kind of critical assessment of the evidence without which science ceases to function. If opposition is absent in the field of nutrition (as it often is), that’s telling. When it’s actually present—per Willett’s quote—but treated as a kind of trivial afterthought, waved off like a mosquito on a hot summer day as the New Yorker writer does, it suggests a deeper, more profound problem.

Before we dig in to the issues with the UPF science and the NIH experiment, though, I have to acknowledge conflicts of interest, or at least potentials for bias.

I have had significant interactions with many of the principals in the story, most notably Kevin Hall of NIH. We were introduced in 2009 by an obesity/diabetes researcher at Penn who was aware of our overlapping interests. I worked with Hall when the non-profit I co-founded (the Nutrition Science Initiative) funded a pilot experiment on which he became one of two principal investigators. I disagreed, publicly and privately, with Hall’s interpretation of that work.2 I’ve written or been a co-author on critical letters--here, for instance--responding to articles that Hall has written criticizing my work, either implicitly or explicitly. I am also a co-author with Hall on a recent paper about obesity pathogenesis (i.e., the cause) and how our perspectives differ.

Our conflicts have been many and occasionally heated. The last time we spoke at length—at a Fall 2023 Symposium in Copenhagen that resulted in the obesity pathogenesis paper—we agreed that we wouldn’t take personally public criticism of each other’s work. My fingers are crossed.

I have also known Walter Willett since the mid-1990s and have criticized his work publicly and argued with him privately. We have also been co-authors on four articles since 2018. On some issues we agree, on some we very much don’t.3

The benefits and risks of trading off expertise for skepticism

The context of these articles on ultra-processed foods is that the concept is new enough (it’s not, as I discussed in my first post on bad health journalism, although the terminology is), and sufficiently unexplored that maybe now nutritionists have finally discovered the real cause of the obesity and diabetes epidemics, If they can finally understand the mechanism of this cause-and-effect relationship—why, in effect, modern industrialized foods have fueled the unprecedented increase in obesity and diabetes prevalence—they’ll know how to curb the epidemics. It’s Hall’s study that is then put forth to likely provide that necessary understanding,

None of the recent articles, though, address the evidence critically, although the New Yorker article comes closest to suggesting that such a critical assessment is necessary. If Hall and his colleagues are fooling themselves (borrowing from Richard Feynman) and so us, as Willett’s comment implies, we can expect that the New Yorker will tell us why.

Moreover, the author, Dhruv Khullar, is a physician who is intimately aware of the obesity epidemic and the cost to individuals and society. In a New Yorker article published last January on the Ozempic revolution, he wrote that he had considered as a young doctor devoting his career to “fighting obesity.”

I interned at a tobacco-control organization hoping to apply the lessons of one public-health campaign to another. I shadowed an obesity-medicine doctor, took classes on food marketing and food addiction, and researched the causes of childhood adiposity. Over time, though, I became disillusioned. Whereas the harms of smoking can be traced to tobacco and the companies that peddle it, obesity is tangled up in our food, jobs, culture, education, and neighborhoods.

Now, he’s an associate professor at Weill Cornell Medical College, director of its Physicians Foundation Center for the Study of Physician Practice and Leadership, and associate director of the Cornell Health Policy Center. He also publishes research on “value-based care, health disparities, and medical innovation.”

He has been moonlighting (if we can call it that considering he’s publishing regularly in the New Yorker) as a journalist since 2013. And he still has time, as implied by the latest article, to “try to cook healthy dinners for [his] three kids.” His ability to multi-task or multi-task and manage his time efficiently is something I can only, if barely, imagine.

Moreover, by seeking out and interviewing skeptics of the UPF concept and critics of Hall’s research, he’s aware that their skepticism and criticism has at least some validity. But he repeatedly refuses to engage with the implications.

Some of the best medical writing for decades have been done by working physicians with accomplishments and day jobs similar to Khullar’s. The New Yorker seems to seek out and collect such writers: the late Oliver Sacks, for instance, of Awakening fame, Jerome Groopman (How Doctor’s Think), Siddharta Mukherjee, (the Pulitzer-Prize winning Emperor of All Maladies), and Atul Gawande (The Checklist Manifesto). I’m likely missing half a dozen more.

These physician/journalists have proven to be thoughtful communicators of complex subjects, but their chosen subjects, for the most part, do not require the kind of profound skepticism of authority that, in my youth, defined the character and sensibilities of a newspaper reporter. Perhaps because of their day jobs, these physicians believe that they should respect the expertise of their fellow experts. Hence, they do, even when they recognize, as Khullar does, that the supposed experts have profoundly different opinions about what’s right and what’s not, which in turn suggests that whomever is wrong in these conflicts is unlikely to be an authority whose expertise we should trust. It’s a tricky business.

Some subjects simply demand a skeptical approach. They can reveal themselves in a single statement from a source: “worse than meaningless….” They require a reporter/journalist/writer who will go beyond describing what is happening, and do what’s necessary to answer the question of why it’s happening?4 This requires a different mindset and so, perhaps, a different skillset.

Now we’re talking about an investigation, and the skills that characterize investigative reporters are entirely different than those of the medical writers. The investigative reporter seeks out the story in the disconnect between what the authorities are saying and what may very well be the reality. That disconnect becomes the story, not just the reality that the authorities are missing or perhaps even hiding, but why they’re missing it or hiding it. Hence, the reporter can’t trust the authorities to have gotten it right, the expertise of the experts, because those authorities might be responsible.

Khullar, as I said, is plenty aware of the problems with modern nutrition research, with the UPF story, perhaps even with Hall’s research. His discussions with critics of this science, he says, have him “vacillating between excitement about the utility of a burgeoning theory and pessimism about its seeming futility.”

But he shows no interest in asking why such a situation would exist, nearly thirty years after we became aware that an obesity epidemic was in the works, and certainly no interest in asking who might be responsible. When a science fails to give us the answers we need to resolve a public health crisis, is it because the job is too hard to do and reliable answers too hard acquire, or because the researchers failed to do their job?

Ultra-processing and the questionable revelations of 21st Century thinking

In Khullar’s 2023 article on the Ozempic revolution, he told the story of the obesity epidemic from the perspective of an “industrial food complex” that had hooked us on overeating “by exploiting our inability to control our cravings.” “Too often,” he wrote, “obesity has been blamed on bad choices. In truth, it is a condition that, perhaps more than any other, has been manufactured by modernity.”

In this month’s article on ultra-processed foods, Khullar picks up the same theme: UPFs are the foods manufactured by modernity, created by industry to exploit our cravings.

Khullar takes the UPF story back to its origin in the early oughts, when the Brazilian epidemiologist Carlos Monteiro was studying malnourished plantation workers in rural Brazil. Monteiro then moves to Sao Paolo assuming he will focus his career on malnutrition and instead is confronted by a seeming contradiction: “around a million Brazilians were growing obese each year,” but “[s]trangely, a shrinking number of people were buying ingredients that doctors blamed for the epidemic such as sugar, salt and oil.”

Rather than assume that maybe the doctors were wrong in focusing on sugar, salt and oil as the cause of obesity (those weren’t the only viable suspects/hypotheses, then or now), or that the epidemiological association between growing obesity rates and the shrinking number of people buying sugar, salt and oil sheds precious little light on cause and effect, Monteiro comes up with another hypothesis:

[h]ouseholds that bought less salt weren’t eating less salt. They were no longer cooking. A good share of their meals arrived in a package. `The issue is not food, nor nutrients, so much as processing,’ [Monteiro] writes in a landmark 2009 paper.

The more processing, as Monteiro sees it, the more fattening the food, and so the more deadly.

With his colleagues, Monteiro comes up with the NOVA Food Classification System: four categories from unprocessed or minimally processed (nuts, eggs) to processed culinary ingredients (oils, cane or beet sugar, but no additives), processed foods (industry manufactured, with added sugar, salt and fat), and ultra-processed (rife with industrial ingredients and additives).

The gist of it, as Khullar explains: “If you can’t make it with equipment and ingredients in your home kitchen, it’s probably ultra-processed.”

And now, if you care to look, you can see how the NOVA classification teeters on the brink of pseudoscience.

For instance, the pizza you make at home, from scratch, is not considered ultra-processed. It could be minimally processed (category 1) or processed (category 3), depending on the cheese and tomatoes you use. A pizza you buy frozen or order from Papa Johns or Pizza Hut is ultra-processed because, well, it’s assumed to contain more industrial ingredients (preservatives or flavor enhancers, albeit not the kind of flavor enhancers you might use at home and are traditionally known as spices), and the flour will be more highly refined, even if it’s not.

If you put pepperoni or sausage, though, on your homemade pizza, it will become ultra-processed because the pepperoni or sausage are assumed to be ultra-processed. Although they might not be if you live in Italy (or even New Jersey) and make them in your kitchen. Then you can add them to the pizza and the pizza is no longer ultra-processed.

Hamburgers are not ultra-processed if you make them at home from ground beef, but they can be if the meat includes other “animal products made from remnants.” They are ultra-processed if you buy them frozen at the store or, heaven forbid, at McDonald’s, even if you neglect to eat the bun and scrape off the condiments.

Confused? The key is that the number of ingredients, the chemical nature of the ingredients, and where the ingredients were added to the foods and where it was prepared determines their category in the NOVA system and, by implication, how deadly or perhaps fattening they happen to be.

As we’ll see shortly, the macronutrient content of the food—the carbohydrate, protein or fat content—is considered less than relevant.

This is the case despite the anecdote with which Khullar begins his article. It’s about a Frenchman who moves to America and becomes a subject in Hall’s experiment and makes the kind of obvious comment that should have us all wondering, “why UPFs?” He tells Khullar that immediately upon relocating to the U.S., he noticed that the food is different here—“Bigger portions. Too much salt. Too much sugar.”

The UPF concept shrugs off that kind of simple observation (and with it Occam’s razor) to implicate the processing specifically; not too much salt or sugar, but all the other ingredients, additives, and means of processing that anchor the food to its industrial source.

“Monteiro’s peers were not immediately convinced,” Khullar tells us, for which we can be thankful.

The idea that any single paper in science would convince anyone immediately of anything is a frightening thought. If nothing else, the results of an experiment might be considered interesting, but the researchers should be wondering if the results are reproducible, for starters—i.e., did the researchers do a good job—and questioning the interpretation of the evidence. And Monteiro wasn’t doing experiments; he was proposing a theoretical concept of a kind that researchers in most scientific endeavors are likely to ignore for as long as they can, if not indefinitely (as implied by the notion that science progresses funeral by funeral).

This is where Kevin Hall comes in:

In 2015, Hall, the N.I.H. researcher, attended a conference on obesity and presented research into low-fat and low-carbohydrate diets.5 After he left the podium, some Brazilian nutritionists approached him. “‘That’s a very twentieth-century way of thinking,’” he remembers them telling him. “‘The problem is ultra-processed food.’” The term sounded nonsensical. Nutrition is about nutrients, he thought. What does processing have to do with it?

That Hall wondered what processing has to do with it seems hard to believe. Nutritionists have been discussing the processing of grains as a key factor in healthful diets since the Second World War, if not before. By the 1960s, British researchers were speculating that the refinement of modern foods—grains, again, and sugar--caused obesity, diabetes and the chronic diseases that associate with them. Any dietary advice that specifies “whole grains” is implicitly doing the same.

But now we’re talking about two different processing scenarios/hypotheses. In what the Brazilian nutritionists dismissed as 20th Century thinking, it’s the processing and then consumption of grains and sugars specifically that cause obesity and diabetes and other chronic diseases. They do so perhaps by making people eat too much, and perhaps by changing the hormonal milieu of the body to affect how it partitions the fuels it takes in, whether we store these macronutrients as fat primarily or use them for fuel.

In the UPF scenario (i.e., 21st Century thinking), the processing of the macronutrient matters little if at all. It’s the processing of the entire food that does the damage and, indeed, even the context of where that food was processed.

Let’s pretend this is science and think about pizzas

A simple way to test these hypotheses would be to go back to our pizza example. It gives us two variations of the same foods and same macronutrients, only one is relatively unprocessed (cooked in the equivalent of a home kitchen) and one is ultra-processed (either frozen or fresh from the Pizza Hut ovens).

We can imagine randomizing subjects for a year to eat every day for lunch either the UPF pizza or the home cooked, relatively unprocessed version. If we deliver the pizzas hot and in the same boxes (baking the “home-cooked” pizza in the research laboratory version of a home kitchen), the participants in the trial shouldn’t know which of the two they are eating. If we run the experiment long enough and the processing matters (not the macronutrients and their processing), we should see a difference in how their bodies and appetites responded to the processing itself. We can trust that’s what we’re observing because we’ve controlled for the maconutrient composition, and we’ve controlled for how the subjects might think about these foods, healthy or unhealthy, consciously or unconsciously, by blinding them to which pizza they’re getting.

To be fair, even Montiero and his colleagues would probably not expect to see any meaningful difference from this kind of controlled trial, no matter how long the duration. Whatever else the subjects were eating would probably dominate the effect of the processing of the pizzas.

But the point, I hope, is clear. We can design experiments that control the variables tightly enough such that an experimental scenario is created has a reasonable chance of differentiating between hypotheses. One hypothesis predicts that if we do this experiment, we’ll see that result. The other one doesn’t.

As far as I can tell, though, that’s not how Hall was thinking when he set out to do his initial UPF experiment. Or perhaps he was just constrained by a reality from which we’re freed by thought experiments.

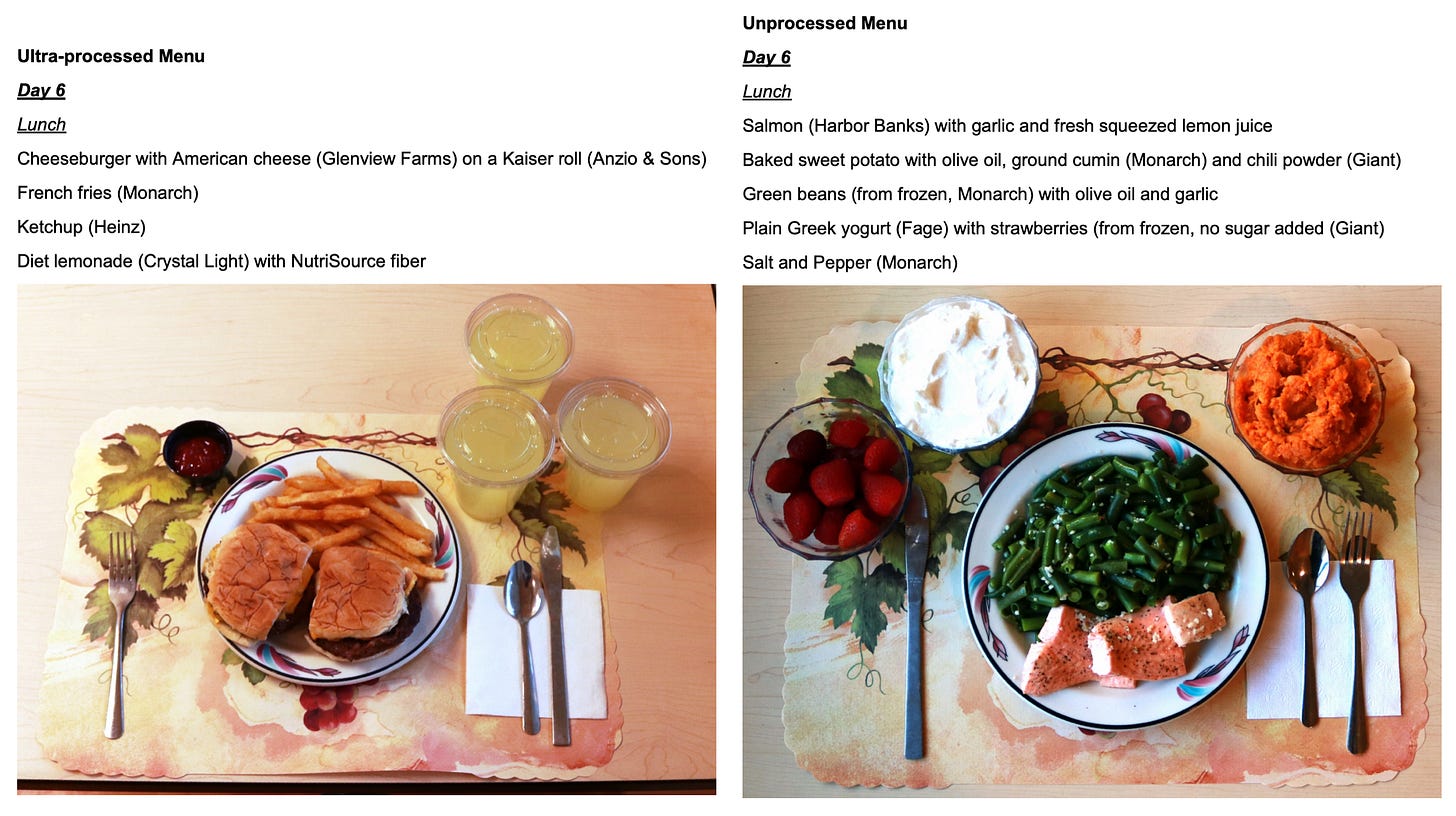

As Khullar tells it, Hall invited 20 people to spend two weeks in his metabolic ward at NIH eating healthy unprocessed foods—“salmon and brown rice”—and then two weeks eating a diet in which 80 percent of the calories came from ultra-processed foods.

We’re told that Hall expected that the two different diets would produce no observable differences in either eating behavior or physiology—Hall’s hypothesis—but that’s not how it turned out.

Hall ended up refuting his own hypothesis. When participants were on the ultra-processed diet, they ate five hundred calories more per day and put on an average of two pounds. They ate meals faster; their bodies secreted more insulin; their blood contained more glucose. When participants were on the minimally processed diet, they lost about two pounds. Researchers observed a rise in levels of an appetite- suppressing hormone and a decline in one that makes us feel hungry.

Hall speculates that the difference is not because “their bodies secreted more insulin; their blood contained more glucose,” both of which would suggest a response to the refining of the carbohydrates in the meals (20th Century thinking), but rather that the UPFs are hyper-palatable and energy dense, two concepts I’ll let Khullar define and I’ll get to at greater length shortly.

It wasn’t clear why ultra-processed diets led people to eat more or what exactly these foods did to their bodies. Still, a few factors stood out. The first was energy density—calories per gram of food. Dehydration, which increases shelf life and lowers transport costs, makes many ultra-processed foods (chips, jerky, pork rinds) energy dense.6 The second, hyper-palatability, was a focus of one of Hall’s collaborators, Tera Fazzino. Evolution trained us to like sweet, salty, and rich foods because, on the most basic level, they help us survive. Hyper-palatable foods—combinations of fat and sugar, or fat and salt, or salt and carbs—cater to these tastes but are rare in nature. A grape is high in sugar but low in fat, and I can stop eating after one. A slice of cheesecake is high in sugar and fat. I must eat it all.

And this is what Hall apparently confirms in his newest study, the results of which have yet to be published. As Khullar tells us, Hall presented the preliminary results at a recent symposium in London, telling the audience that the subjects ate 1000 calories a day more of an ultra-processed diet that was particularly hyper-palatable and calorie-dense than they did unprocessed food.

But when the team served ultra-processed foods that were neither calorie-dense nor hyper-palatable—for example, liquid eggs, flavored yogurt and oatmeal, turkey bacon, and burrito bowls with beans—people ate essentially as much as they did on the minimally processed diet. They even lost weight.

The implication: it’s the ultra-processing and perhaps, specifically, the calorie or energy density of the food and/or the hyper-palatibility that makes people eat too much.

Again we’re drifting dangerously close to the shoals of pseudoscience here. I can understand why Khullar doesn’t get into these issues—it can set heads spinning, as you’ll see-- but it would be nice if he had.

Khullar does say that talking to skeptics left him occasionally pessimistic about the “seeming futility” of this research, but the skeptic he quotes, Alan Levinovitz, a professor of religion at James Madison University who has written books on nutrition subjects, has other issues than pseudoscience in mind. Levinovitz tells Khullar that research on UPFs is a “colossal waste of money,” not because it’s worse than meaningless, as Willett was saying, but because we “already know why populations are gaining weight: ubiquitous, cheap, delicious, calorie-dense foods.” Hence, we had turned “what’s staring us in the face into some kind of research question.”

That’s certainly a problem if Levinovitz is right about “why populations are gaining weight,” but he might not be. So onward with the explanation.

Hyper-palatability and energy density: science or sort of science?

Calorie (or energy) density, as Khullar says, is a measure of the number of calories contained in a unit of weight: i.e., calories per gram. The connection with obesity dates to the 1980s, when Barbara Rolls, a behavioral scientist/nutritionist then at Johns Hopkins, reported that people seemed to eat the same weight of foods at a meal, regardless of the calories. Hence, the more calories per unit of weight, the more people would eat. In short, energy-dense foods make us fat. We don’t realize how many calories we’ve consumed until it’s too late and we’ve overeaten.

The idea caught on, possibly because foods that aren’t energy dense include leafy greens, other non-starchy vegetables and fruit, foods that nutritionists think of as healthy and supposedly make us “feel full on fewer calories,” which was the subtitle of the self-help book, The Volumetrics Weight-Control Plan, that Rolls then wrote about this concept. (Many of us who eat salads for lunch or dinner do so, whether we know it or not, because of Rolls and her research.)

But energy-dense foods also notably include cheese, butter and fatty meats—the stuff of ketogenic weight loss diets—and also cookies, crackers and ice cream (and the cone).

Full fat yogurt is energy dense because of the dense calories in the fat. Low-fat yogurt is not, because the calories are diluted by water.

Sugary beverages are not energy dense because those sugar calories are also diluted by water.7

The implication of Hall’s research, though, and the UPF story is that it’s energy density that determines how many calories we consume, and therefore how fat we get and how healthy (or not) the foods. Once again, it’s not the macronutrients per se (the sugar, flour, fat, oils, etc) and not how those macronutrients are processed, but the energy density of the foods themselves.

All of this can be tested by experiment, but… 20th century thinking.

Now, sugary beverages may be unhealthy despite not being energy dense, but because they might be ultra-processed (Coca Cola, or lemonade purchased in a bottle or can at the market), although not always (lemonade made at home, from water, lemons and sugar). Worse, they could be ultra-processed and hyper-palatable.

Hyper-palatable is a five-dollar word that means the food is delicious. Although, per the lens of the UPFs and 21st century thinking, it is reserved only for foods that are sold in packages by the food industry and not foods we cook at home or that great chefs might cook in their 2-star-or-more restaurant kitchens. Macaroni and cheese at Murray’s Cheese Bar in New York or Parkside in Austin: delicious. Kraft mac and cheese or macaroni and cheese made at home with Kraft’s cheese: hyper-palatable. The former we eat because they taste so good. The latter, because they exploit our cravings.

Pizza made from scratch at home: delicious. Pizza purchased frozen at the supermarket or out of the oven at Pizza Hut: hyper-palatable. Go figure.

Hyper-palatability implies that it’s the industrial processing of the food (the preservatives, (non-spice) flavor enhancers, etc) and its ability to exploit our cravings that matters, not the macronutrients being processed (the sugar, carbohydrates or fats). And this difference matters because it determines how much people eat and so how fat they get. Not because of the physiological effects the food has in the body, unless those physiological effects come from the additives. Are you following?

Considering the bated breath with which the nutrition community and the media are awaiting the official results of Hall’s newest study, we can hope that he takes all this into account and controls for all these possible competing variables—the macronutrients and their processing vs. the hyper-palatability and the energy density.

But he didn’t do that in his last study, the one that’s the most influential of the last five years, which brings us back to the Willett quote that launched this post.

To be precise, Khullar quotes Willet saying of studies “like” the one that Hall published in 2019 that they are “worse than meaningless—they’re misleading.” (My italics.) But I think Khullar is doing subtle damage control here. Had we known that Willett had said such a thing about Hall’s study specifically, we might have wondered why we were reading a story that spent so much verbiage discussing Hall’s research uncritically. At the least, we’d want to know why Willett had said such a thing. Give us the details. Give us the implications.

And Willett very likely did say that about Hall’s 2019 study specifically, because he made that point explicitly when he co-authored a letter to the editor about Hall’s 2019 study that described why it was misleading and so worse than meaningless. Willett was the last of seven very influential academic nutritionists who co-signed the letter. David Ludwig, of Harvard and also the Steno Diabetes Center in Copenhagen, was the first author and the “corresponding author,” which implies Ludwig did the bulk of the writing. Khullar, though, does not seem to have reached out to Ludwig to discuss it.

As Ludwig, Willet et al said in that letter:

On first pass, the primary findings of this 2-week study do not surprise us. Confine U.S. volunteers interested in a food study to a metabolic ward, give them unlimited access to processed foods that appeal to the American palate, allow them to eat as much of them as they like, and some will overeat. The critical questions are: What is driving food intake? Does this effect have relevance to the chronic control of body weight?

They then delve into the many reasons why Hall’s study failed to answer these questions: Why it was misleading, and so worse than meaningless. What they call the critical questions are, well, the critical questions.

It’s quite possible that what was driving food intake and weight gain in the study was the processing of the macronutrients and specifically the carbohydrates (that 20th Century thinking), not the number of additives or the type of additives, and so the ultra-processing (21st thinking).

On the “ultra-processed” versus “unprocessed” diet, participants ate substantially more total carbohydrate, added sugar, saturated fat, and sodium, and less protein, polyunsaturated fat, and soluble fiber. Non-beverage energy density was 85% higher on the ultra-processed diet. Moreover, at 45 g per day, the unprocessed diet had almost triple the intrinsic fiber of an average Western diet. Each of these factors, previously linked to food intake or metabolism, may have influenced the study findings independently of food processing.

An important observation was that Hall’s subjects seemed to be eating less of the ultra-processed foods as the days went on. The difference in calorie consumption on the two diets was diminishing with time.

We can never know in these studies what would happen after they end, but it’s reasonable to speculate that had the study lasted more than 14 days, the difference in how many calories the subjects consumed would have vanished.8 And had the subjects known they were gaining weight, it might have vanished quickly.

These speculations speak to the second of the critical questions raised by Ludwig, Willett and their co-authors: Does the effect of whatever is driving food intake “have relevance to the chronic control of body weight?”

Khullar doesn’t address this, but it lies at the heart of obesity science. There should be no getting around it.

The reason why Hall’s 2019 study is so influential is largely because of how it has been interpreted: ultra-processed foods make people fat and they do so, presumably, by making people eat too much. If nothing else, if people just ate unprocessed or minimally processed foods they would not eat too much, not get fat, perhaps even lose weight, and the obesity epidemic would be resolved.

The title of Hall’s article said it all: “Ultra-processed diets cause excess calorie intake and weight gain.” And while this was technically true in the context of Hall’s study, the study could not unambiguously identify the ultra-processing itself as the reason for either consequence—eating excess calories and weight gain.

Still, the assumption and the reason for the study’s influence is this chain of events:

Ultraprocessing —> Excess calorie intake (i.e., overeating) —> weight gain.

But, once again, we’re left asking a few simple questions, beginning with what if the study had lasted more than two weeks?

Another version of this is, what happens if we assume that what happened in Hall’s study when people eat ultra-processed foods is what happens in the real world? This is, after all, why Marion Nestle thinks Hall’s study alone gives us the evidence necessary to implicate UPFs in the obesity epidemic and suggest people avoid eating them.

As people get fatter eating the excess calories of UPFs—either in Hall’s study, had it gone longer than two weeks, or in the real world—why wouldn’t they cut back and eat less? Why would they continue to eat too much, despite all the significant psychological, social and health burdens of obesity?

The point I’m making is similar to one made by the Boston University obesity medicine specialist Caroline Apovian on 60 Minutes a year ago, but the difference is telling.

Here’s what Apovian said:

Don't you think if people walking down the street with obesity, stigmatized as they are, shunned, don't you think if they could lose weight and keep it off they would?

And here’s the question implied by the interpretation of Hall’s study:

Don't you think if people walking down the street with obesity, stigmatized as they are, shunned, don't you think if they could eat less and keep eating less they would?

The implication of the way Hall interpreted his research is that the two statements are equivalent. But they’re not. They’re only equivalent if eating too much is why people get fat. And it may not be.

We can imagine why, as Apovian implied, people might have trouble losing weight and keeping it off, even when stigmatized and shunned. They might have little control over their body weight.

But eating less? A little less? Enough to not get fatter? Why not?

What’s more, many of Hall’s subjects were not obese. Their average body mass index was 27. At some point they wouldn’t need a scale to realize they were getting fatter, inching their way toward obesity, and then they could cut back. Why wouldn’t they?

The consensus of opinion among obesity researchers and obesity medicine specialists is that two facts about body weight are indisputable:

1. We get fat because we eat too much—we consume excess calories.

2. Obesity is not caused by personal misbehavior (“bad choices,” as Khullar wrote) or a lack of willpower, as an essay in The New York Times explained in 2022.9

Put these together and you have his proposition: body weight is controlled by how much we eat, but whether we eat too much or not is beyond our conscious control. The idea is that our brains determine how much we fat we carry and they do so primarily by regulating our food intake. If our brains, for whatever reason, want us to be fatter, we cannot stop the effect on our food intake. This is how Hall and 11 very influential co-authors described this concept in 2022 (with my italics):

…the brain is the primary organ responsible for body weight regulation operating mainly below our conscious awareness via complex endocrine, metabolic, and nervous system signals to control food intake in response to the body's dynamic energy needs as well as environmental influences.

The implication of Hall’s latest studies and of Khullar’s article (and its ilk in the Times, the WSJ, the Economist) is that ultra-processed foods are the environmental influence that has driven body weights inexorably up. And the hyper-palatability and energy density of UPFs are why they work “below our conscious awareness” to make us eat too much. They exploit our cravings.

That thinking, though, requires that we never know that we’re eating too much, because once we do, the failure to cut back, to eat less—even if just by half a sandwich or a glass of orange juice a day—seems a hell of a lot like a lack of willpower. And we must know when we’re eating too much, by this thinking, because that’s what’s happening if we’re getting fatter.

Moreover, people who remain lean in a world of ultra-processed foods must clearly do this job of controlling their intake. Why is it they can do it and the rest of us can’t? Are their cravings not exploited, or not as much, or do they do a better job of fighting the exploitation?

If the problem with the UPFs is that they somehow make people overeat—by 500 or even 1000 calories a day—why wouldn’t those people stop eating so much once they realized that they are gaining weight?

If the study did continue for longer than two weeks, would self-restraint triumph? And if it didn’t, why not?

We can hypothesize that the food they’re eating is so finely crafted, so hyper-palatable, so calorie dense that the cravings it exploits are beyond their power to control, but clearly some people do resist them, because some people stay lean in an environment (even a house or an apartment or a metabolic ward) that’s full of UPFs, and some people stay lean even while eating UPFs (my youngest son, for instance). We don’t need an NIH research experiment to tell us if that observation is true; we can just look around us.

So what’s the difference between those that stay lean in a UPF-rich world and those that don’t? Insisting that it is not willpower, doesn’t change the fact that it sure as hell seems like it, at least it does if the way UPFs do their damage is by making us eat too much.

On the benefits and risks of ignoring complications

Here’s my answer, as I suggested earlier, to why Khullar didn’t explain the significance of the problems that Willet and Ludwig et al. had with Hall’s study: Had he made it clear why such influential researchers found the interpretation of the research so unreliable, he would negate the rationale for the article. Why, the reader would ask, have I been reading this?

But now we’re confronted with yet another question: in the midst of an obesity and diabetes epidemic that must be related in some way to the food we eat: What’s happening in the field of nutrition that highly influential researchers could differ so completely in their assessment of what is, after all, a fairly simple experiment.10

Throughout his article, Khullar reveals that he’s aware of the problems with modern nutrition research. For instance, he says, even if the thinking on ultra-processed foods should pan out, what difference will it make?

People know that Doritos are not so good for them, but more than a billion bags are sold in the U.S. each year. Who, exactly, will be moved by the knowledge that salty-sweet ultra-processed foods might be worse than merely salty or sweet ones?11

He even acknowledges that obesity researchers and nutritionists have made little progress understanding the problem. There’s a “dirty little secret” in this field, he is told by Dariush Mozaffarian, director of the Tufts (University) Food is Medicine Institute: “[N]o one really knows what caused the obesity epidemic. It’s the biggest change to human biology in modern history. But we still don’t have a good handle on why.”

So why not? Is the science so complicated, or have the researchers doing the science collectively failed to do their jobs. The latter may not be true, but it has to be entertained (investigated?) as an obvious possibility.

If true, isn’t that the story that has to be written?

Why can’t theories halt the epidemic?

I have to make one last point before letting this go. Ultimately Khullar justifies the UPF theory, pessimistic as he occasionally is, on the basis that the dirty little secret implies a high demand for viable theories. “Of course,” he writes, “since no previous theory has succeeded in halting or even fully explaining the obesity epidemic, we need new ideas.”

Now, though, I wonder if Khullar is being uncharacteristically lazy, or if he doesn’t understand the nature of science (ultimately his training is in medicine; he’s just a doctor), or perhaps he doesn’t care. He’s passing along a common sentiment of the nutritionists and obesity researchers, even when it leads him to writing something that I doubt he’d believe in any other context.

Scientific theories do not have effects in the real world.

While a viable theory should be able to explain the obesity epidemic, it cannot halt the epidemic. First, it has to be tested, and if it survives the tests, and the research community agrees that it’s a viable hypothesis or even perhaps the most likely hypothesis, then perhaps its implications can be applied in public health programs that might halt the epidemic.

As Khullar suggests about UPFs, it’s hard to imagine that people will eat differently, even if the theory should turn out to be right. We know Doritos are “not so good” for us, and most of us know if we have a problem eating them in moderation (however we define that). Again, no NIH research program is necessary to tell us that.

Hence a correct theory might not have an application in the real world that makes a damn bit of difference. In such a case, though, we still won’t know if it’s the theory that was wrong or the application of the theory that failed. (Indeed, perhaps by that time the epidemic was beyond halting.)

Theories have an effect when their practical implications are applied. Ideally, this happens after they’re rigorously tested, accepted by the relevant research communities as very likely to be true based on that testing, and then put into action by the public health community in a way that maximizes the efficacy of the knowledge.

Yes, the research community has to be open-minded, but they also have to think critically about the competing theories, and then commit their resources to testing them. Finally, they have to think critically about those tests, because if they’re willing to accept anything to support their beliefs, then we can assume they’re willing to believe anything, whether it’s true or not.

The New Yorker says the study has been cited “nearly 2000 times” since it’s publication, but that must be using Google scholar. The Web of Science, which includes only references from the peer-reviewed academic literature, puts the number at just under 1000.

As did my NuSI colleague Mark Friedman, who published his issues in a letter to the editor that’s worth reading.

Another potential source of bias with this kind of critique is more personal. In the past, critics of the work of exceedingly successful writers—Malcolm Gladwell, most notably—have been accused of being motivated by envy, which is always possible. If Gladwell, for instance, wasn’t remarkably successful, by this logic, these critics would not be so critical. That can always be true, but it isn’t necessarily. In this case, I have never been published in the New Yorker but not for lack of trying. Do I envy those authors who write regularly for the New Yorker? I do. It is, as a friend once said about his job at the New York Times, like getting to wear a magic coat, which makes everyone sit up and pay attention.

I’m echoing here a colleague who once said of a prestigious researcher with whom we were collaborating, “he’s very good with the hows”—i.e., how to make an experiment work—“not so good with the whys.”

This is likely to have been the experiment funded largely by NuSI, the non-profit that I cofounded.

For those reading closely, they’ll notice that potato chips are considered obesogenic, i.e., they make us fatter. Pork rinds are usually evoked in the context of keto, a diet food. They have very different macronutrient composition even if similar energy density. They present another way to set up an experiment to test the competing hypotheses, in which we can control for energy density and vary the macronutrient composition dramatically. Although, again, the results are likely to be dependent on all the other foods in the diet and the physiological context in which the chips or pork rinds are eaten.

If you ask ChatGPT about this, it will tell you that sugary beverages are calorie dense, but if you challenge it with the fact of the dilution, it will agree that they’re not and apologize for misleading you.

It’s also easy to imagine that when the subjects ate less and lost weight on the unprocessed diet, its because they knew the diet was healthy—”salmon and brown rice”—and ate accordingly. (And if the photos of the meals are any indication, particularly the Tyson’s beef tender roast they were serving in several of them, the subjects might have eaten less because it was overcooked and badly in need of a condiment—ketchup or perhaps Worcester sauce—which are, typically and regrettably, ultra-processed foods.) Eventually this effect, too, could diminish. What happens over 14 days tells us precious little about what happens years to decades and obesity is a condition that develops over the latter time scales, not the former.

The author of the NYT essay, Julia Belluz, is now co-authoring a book with Kevin Hall—Why We Eat: Unraveling the mysteries of nutrition and metabolism—that appears to be coming out this year.

Worth noting is that Willett also co-authored a letter (again with Ludwig), published this month, about another of Hall’s papers, a re-analysis of the 2019 study. Now Willett and Ludwig suggested that Hall’s re-analysis was so flawed that they used the word “fatal” to describe it’s implications. They posed four questions to Hall and his co-authors that they thought might clarify the matter. In functioning sciences, authors respond to questions thoughtfully because it clarifies for everyone else, who and what to believe. Hall’s brief response implied only that the questions were unworthy of his time and that Willett and Ludwig were not asking them in good faith.

I can understand why Hall and his colleagues might like to move on. As they say in their response, they have yet another, clinical trial in the works and maybe that will resolve everything. But for those in the nutrition research world who would like to know what (or who) to believe, blowing-off the concerns of critics seems to do a disservice to the science.

According to Khullar, Hall believes his research could help food companies make ultra-processed foods that are healthy, and that the industry would be just as happy to sell healthy UPFs as unhealthy ones. I find it difficult to imagine, though, how that would play out if the secret to making healthy UPFs is to make them less hyper-palatable, and so less likely to be eaten. Those foods already exist, as the article makes abundantly clear, and can also be found in the supermarkets. But people don’t buy them because, well, they don’t like them as much.

I have no problem with the length of your articles, despite Mark Twain apologizing for a long letter, saying he did not have time to write a shorter one. But I understand the need for brevity. I am retired. I sat down in my recliner and read this slowly, absorbing as my capabilities allow, feeling sated after. I wondered why researchers go to such lengths to go around some points that must be addressed if they are being honest: Why were obesity and diabetes not problems before they became problems? The answer surely lies in the diets then and now. What is different? When I was in high school, my medium-sized home town had but one pizzeria and no McDonalds, though a few burger joints were around. Our choices were limited and most cooking was done at home. Those meals in my house were always meat (except Friday), a vegetable, milk and often enough potato. Dessert was for weekends. Soda pop was limited to two bottles weekly. Nowadays I avoid sodas and anything potato, the only difference. I am trim and not ill in any way, knock on wood.

I enjoy the long articles, and I fear that shortening them by much would leave a lot of important information out. They are long, but energy dense. :-)