NIH Has A Nutrition Problem (Part 2 )

If you want to demonstrate that a low-fat diet is better than a ketogenic diet (or that ultra-processed food makes us overeat), these critical design flaws will help.

One basic premise is that it is unethical to conduct research which is badly planned or poorly executed. That is, if a trial is of sufficiently poor quality that it cannot make a meaningful contribution to medical knowledge then it should be declared unethical... an investigator's ignorance of the scientific and organizational needs for a clinical trial should not be seen as an excuse. Stuart Pocock, Clinical Trials: A Practical Approach, 2013

Unethical!? Why unethical?

Pocock, a medical statistician at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, was discussing trials in which whatever harms and inconveniences the volunteers might undergo are weighed against the benefits that could accrue from the research. If the trials are poorly designed, there's no benefit.

But it's worse than that: the only reason to do a trial is to meaningfully contribute to medical knowledge. A poorly designed study subverts that goal. It doesn't just fail to make a contribution; it does the opposite, getting us further from the truth. It inserts a wrong answer into a pursuit that is all about establishing the right one.

This is why studies that are demonstrably wrong are retracted, or at least they should be if the researchers care more about the science than their careers. Correcting the scientific literature when it's known to be wrong is a moral obligation.

In my last post, I discussed two recent articles—an op-ed in STAT and the BMJ article on which it was based—asserting that critical NIH nutrition research was "designed to fail." Specifically, the current flagship of NIH nutrition research—a $170 million initiative, Nutrition for Precision Health (NfPH)—and the most influential nutrition research that has emerged from the NIH in the last decade.

This was the work done by Kevin Hall, who had taken early retirement a week before the articles were published (probably a coincidence). That Hall's retirement was described in the news reports as a "national tragedy"—and that his "landmark" study on ultra-processed foods (UPFs) is cited prominently in this week's MAHA report, Making Our Children Healthy Again—made the assertions in the STAT and BMJ articles all that much more newsworthy and the implications to nutrition research in general all that much more profound.1

That last post discussed the first of two critical, if not fatal design flaws in the NfPH initiative and the trials for which Hall has received such acclaim. Put simply, if we want to establish how diet affects chronic disorders and particularly obesity, having people eat the diet for only two weeks cannot tell us anything meaningful.

This post discusses problem #2. How this one plays out in Hall's research could be a case study in an introductory college course on pathological science: what not to do in an experimental science if you want to avoid having to defend the indefensible.

How much of a problem this is with Hall's UPF study remains to be seen. It is fatal to the interpretation of a trial he published in Nature Medicine two years later, in 2021, comparing plant-based low-fat diets with animal-based ketogenic diets. That one blew up into a years-long controversy that now sheds its light and heat back on the UPF study which is widely touted as providing the one unambiguous truth about the evils of ultra-processed foods. (They make us eat too much.)

Design the wrong study, you answer the wrong question

A critical challenge of any trial examining the diet-disease relationship is getting your subjects to eat what you want them to eat. This problem can be solved by confining the subjects as in-patients in a metabolic ward—as Hall did in his studies and the NfPH will. The study can now be called "tightly controlled," and it’s this tight control that has prompted nutrition policy types to hold Hall's research in such high esteem.

But this is like complimenting the design of a stool because you like the length of one leg. There are others. Metabolic ward studies come with a trade-off: they're expensive. Keeping costs under control requires keeping the study short (another leg of the stool). Hence, two weeks in Hall's study; two weeks for the NfPH initiative to come. The two-weeks-is-too-short problem discussed in the last post.

But now (a third leg) you can maximize the statistical power of your study—get the most bang for your buck—by doing what's called a crossover study. Rather than randomizing your subjects to one of two different interventions—say eating diet A OR diet B—your subjects get both interventions—diet A AND diet B—but in random order. Midway through the trial, they’re crossed over from one intervention to the other. Some get diet A first and then diet B. Others get the opposite.

Hall used this protocol for his landmark 2019 UPF study: housing his patients for four weeks in the NIH metabolic ward, feeding them an ultra-processed diet for two weeks and a minimally processed diet for two weeks, in random order. And Hall used this same design for his 2021 study comparing a plant-based low-fat diet (LF, per Hall's terminology) with an animal-based ketogenic diet (LC, for low carb).

This was the study in which the problems in the design became all too obvious, and they did, quite simply, because this study woke up the critics. Those who appreciated how Hall interpreted his research saw no reason to critique his research. (They still don't.) Those who found the interpretation troubling, naturally wondered why.

Why do researchers criticize the research of others?

Hall's paper implies that he did this study to test a prediction of a way of thinking about obesity that he believes is wrong. This is the idea that carbohydrates are uniquely fattening—a concept that's become known as the carbohydrate-insulin model, or CIM. David Ludwig, a Harvard nutritionist/endocrinologist, gets credit for the model, as do I and others.

Because Hall invariably interprets his research as “refuting” or being “inconsistent” with this CIM thinking, Ludwig has become relentlessly critical of Halls research. This can make Ludwig's criticisms look self-interested and so biased. And it may be why Hall has a tendency to treat any criticism from Ludwig as though he is trolling him on X rather than making important points that need to be addressed. Ludwig was the first author of the BMJ article, along with his Harvard colleague Walter Willett and the Penn biostatistician Mary Putt. Ludwig and Putt wrote the STAT op-ed.

Because Hall believes that obesity is caused by eating too much, he believes the CIM predicts that people will eat fewer calories on a diet that restricts carbohydrates than on a diet that doesn't. (The model makes no prediction on this, but we're going with Hall's thinking here.) Hence, by Hall’s thinking in the Nature Medicine study, feed 20 adult volunteers a very-low carbohydrate ketogenic diet for two weeks and a very low-fat diet for two weeks,2 in random order, assume Ludwig and the CIM are correct, and you should see them eat less of the low-carb diet than the low-fat.

But that’s the opposite of what Hall observes. Put simply, he confirms his preconceptions, not Ludwig’s. Here's how he sums this up in the abstract of his paper:

We found that the low-fat diet led to 689 ± 73 kcal d−1 less energy intake than the low-carbohydrate diet over 2 weeks (P < 0.0001) and 544 ± 68 kcal d−1 less over the final week (P < 0.0001). Therefore, the predictions of the carbohydrate–insulin model were inconsistent with our observations. [My italics]

Not surprisingly, this gets Ludwig's attention. If Hall was interpreting his research correctly, then Ludwig is wrong (as am I): Not only are carbs not uniquely fattening, as the carb-insulin thinking implies, but diets that restrict animal products and dietary fat might be a better way to lose weight than those that do the opposite, as ketogenic diets do to extremes.

Ludwig's initial concern (as was mine) was that two-weeks-is-too-short problem. But that's all backstory (as they say in the movie business).

What about that allegedly fatal flaw?

In 2023, Hall posted a draft of an article (a preprint) acknowledging a significant issue with both his recent studies. This was problem #2 pointed out in the STAT op-ed and the BMJ article. Hall gets credit for pointing this out.

Here’s the study design, as diagrammed in Hall’s 2021 Nature Medicine paper:

For those who design studies for a living (i.e., where were the peer reviewers on this NM paper?), the problem should have been obvious. The subjects in Hall's studies go directly from eating one diet to eating the next. They don't finish eating one diet, take a break for a few weeks or even months—technically known as a wash-out period—and then start on the second diet. They go directly from the first diet to the second.

That means how the subjects adapt to the diet they eat second—both physiologically and perhaps psychologically—is a response to the diet they ate first. That effect might be minimal, but it's going to exist. The second diet is consumed in the context of the diet that preceded it.

Hall was not comparing what happens when his subjects eat a very low carb diet or a very low fat diet, as he thought he was. He was comparing what happens when his subjects switch from very-low-fat to very-low-carb diet with what happens when they switch from very-low-carb to very-low-fat. He was comparing the transition from one diet to the other and vice verse, not the diets themselves.

In his Nature Medicine paper, Hall wrote that this carryover effect (the technical term) from one dietary period to the second was “not significant” and could be ignored.

But at some point after publication of that article, he realized that maybe it wasn't and reassessed the size of the effect, now using the correct calculation. This is what he published in that preprint and in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition last October.

The new analysis implicitly acknowledged that cross-over studies require a wash-out period between the diets. Feed the subjects some control diet (perhaps whatever they were eating pre-trial) and do it for long enough that the effects of the first diet have dissipated before the subjects start the second. That way you can compare what happens on the second diet to what happened on the first without worrying about how the first diet may have influenced their response to the second.

Hall had an excuse for designing his study without a wash-out period:

In our experience, washout periods in inpatient crossover studies increase risk that participants withdraw from the study before completing all interventions, and our most recent inpatient crossover studies, therefore did not have washout periods.

But it wasn't a good excuse, as Ludwig, Willett and Putt would point out in their critiques. Biostatisticians, like Ludwig's co-author Mary Putt, trial designers and even federal health agencies, had been insisting for decades on the need for wash-out periods between diets or drug interventions in these cross-over studies.3 (Look at the limitations and disadvantages section of the Wikipedia entry on "crossover studies" and you'll wonder why we’re even discussing this.)

Hall's new analysis then made an attempt to assess how big a problem this lack of cross-over presented. His conclusion: it was huge for the low-fat vs low-carb study:

Diet order significantly affected energy intake, body weight, and body fat in a 4-wk crossover inpatient diet study varying in macronutrients.

But Hall also concluded that despite this huge confounding effect, it somehow was not meaningful enough to revise their conclusion from the first paper, let alone retract it, and it appeared small enough in the landmark UPF paper to be irrelevant there.4

Ludwig and his collaborators readily agreed it was huge—that was undeniable—but disagreed about the implications for the findings and for the landmark UPF study.

What do we mean by huge?

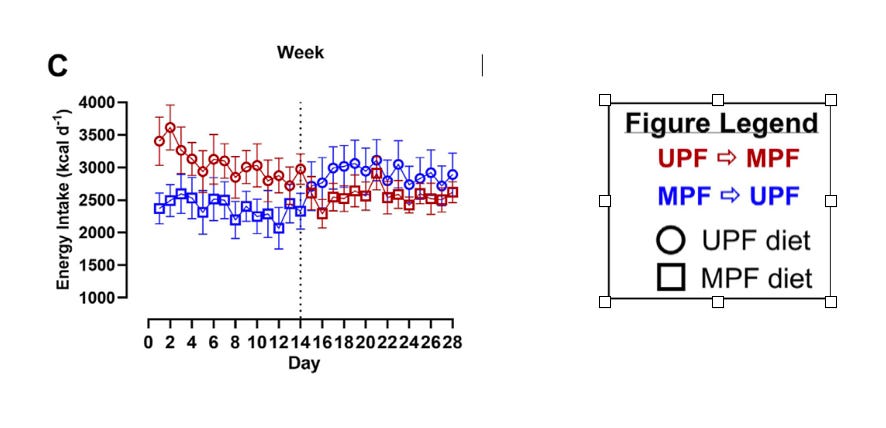

Well, take a look at Figure 2C from Hall’s paper:

Let me explain what you’re looking at. The red, per the legend, is the average of how many calories were consumed per day by the subjects who ate the low-carb ketogenic diet first, followed by the plant-based low-fat diet. The blue are subjects who ate the low-fat diet first, and then the low-carb diet after.

What makes this confusing is that the low-fat diet is blue in the first two weeks and red in the second. The low-carb diet is red in the first two weeks and blue in the second.

Here’s the same figure broken up into the four separate weeks so we can see clearly what Hall observed:

In the first week, when the subjects embark on the study and their first diet, they consume roughly the same amount of calories, regardless of diet—whether low-carb or low-fat. The low-carb diet might have a little advantage in that people seemed to eat a little less.

Since Hall says the carbohydrate-insulin model predicts subjects will eat less on the low-carb diet (deferring again to his thinking), this very slightly favors that prediction.

In the second week that advantage increases: now the subjects eating a low-carb diet are eating a few hundred calories a day less than the low-fat diet. So by Hall's assessment, Ludwig's carbohydrate-insulin thinking is still panning out.

Then they cross over.

Now look at weeks 3 and 4: After the crossover, the difference between the amount of calories consumed on the two diets explodes. This is quite literally the effect of the crossover—the carry-over effect.

Subjects who go from eating a very low-carb diet to a very low fat diet are eating maybe 2000 calories/day less than the subjects who go from eating the low-fat to the low-carb. This is what I meant by huge.

In week 4, that difference is still huge, but slightly less so. Combine those last two weeks together, as Hall does, and the difference is 1600 calories/day, now hugely in favor (per Hall's thinking) of the low-fat diet.

Combine that 1600 calorie/day carry-over effect favoring low-fat with the (relatively) small difference before the crossover favoring low-carb, and you get the ~700 calories per day that Hall reported in his paper as being inconsistent with Ludwig's thinking. That difference, and so Hall’s conclusion, is a consequence of the carryover effect.

After Hall posted the preprint of his diet order analysis, I can imagine Ludwig and his colleagues thinking to themselves something along the line of "holy [fill in preferred expletive here]! This is far worse than we thought."

The result: Ludwig and his colleagues published their own re-analysis of Hall's publicly-available data, confirming Hall's re-analysis, but now with a very different interpretation of the meaning:

These findings, which tend to support rather than oppose the CIM, suggest that differential (unequal) carry-over effects and short duration, with no washout period, preclude causal inferences regarding chronic macronutrient effects from this trial.

This was followed by the series of letters-to-the-editor—punch and counterpunch—that went back and forth between Ludwig et al and Hall et al (here, here, here, and here) and has so far culminated with the BMJ and STAT articles.

What both sides agreed on, oddly enough, is that the carry-over effect, which Hall had asserted in the first paper was not significant, was precisely the opposite.

In his Nature Medicine paper, Hall had asked a simple question about how to explain what he had observed: why his subjects consumed so many fewer calories of the low-fat diet than the low-carb:

What was the mechanism for the reduced ad libitum energy intake in the LF diet compared to the LC diet?

And Hall had suggested several possibilities: Maybe the greater fiber content and "substantially lower nonbeverage energy density" of the low-fat diet were responsible. Both, per conventional thinking, would increase satiety and so decrease food intake.5

Now he had provided the answer: the "reduced ad libitum energy intake in the LF diet compared to the LC diet" was not an effect of the diets consumed, as Hall had assumed. It was what happens when you do crossover study without the requisite wash-out period. It was the carry-over effect.

Hall wouldn't say as much, but he acknowledged it certainly could be:

The presence of a significant difference between the LC → LF compared with LF → LC groups, indicates a carryover effect that is difficult to disentangle from the LC compared with LF diet effects.

One way or the other, as Ludwig et al argued, the only data that could be disentangled from the carry-over effect—the only data that could be trusted—were the data from before the crossover. Those data favored the low-carb diet.

The obvious question: Should Hall have retracted the Nature Medicine paper?At best, after all, the disentanglement problem made his assertive statements in that paper false? In an ideal world (mine, although apparently not Hall’s), he would have retracted his own paper after publishing the 2023 re-analysis and been done with it. He'd have been given credit for cleaning up his own mistakes, one of the best things a scientist could do, and he could move on with his research.

Meanwhile, Hall's Nature Medicine paper has been cited over 140 times, more than 20 times since he published his re-analysis in AJCN revealing the enormous carryover effect. That re-analysis has been cited only by Ludwig and Hall himself in their LTE’s.

Researchers are aware that letters-to-the-editor tend to go ignored with time. Published studies not so. Retracting a paper is no guarantee that thoughtless researchers in the future won’t cite it, but it makes it harder to to do.

What about that landmark UPF paper & the NfPH Initiative?

That 2019 UPF study, after all, is the reason for Hall’s extraordinary influence in nutrition. In his re-analysis Hall claimed that the carryover effect for the UPF trial was, well, not significant. He suggested it only existed when comparing diets of different macronutrient content. Can that assertion be trusted?

Ludwig, Willett and Putt say no. The carryover effect may not be "visually apparent" as it is in the LF-LC trial, but that doesn't mean it's not significant. Putt had published an analysis twenty years ago suggesting that the kind of post-hoc analysis Hall was doing was incapable of ruling out significant carryover effects. So maybe Hall is right and carryover effects are insignificant in UPF studies, but if nutritionists are serious about understanding the dangers of UPFs, they wouldn’t trust it.

In the last LTE that went from Ludwig, Willett and Putt to Hall, they suggested the carryover effect was "fatal" to Hall’s LF-LC trial, and concluded with two simple questions they hoped Hall would be kind enough to answer about his UPF trial:

Do the authors [Hall et al.] agree that their analysis cannot exclude the presence of a clinically important carryover effect in this trial and the resulting bias on analyses of the primary dietary effect? If not, why not?

In Hall's brief response, he neglected to answer.

They were, though, the critical questions.

But, surely, future trials will avoid this (allegedly) fatal flaw?

Short answer: no. While the new MAHA report, released on Thursday, focuses on ultra-processed food as a primary driver of chronic disease in this country, the one clinical trial that NIH has in the works on UPFs (according to clinicaltrials.gov) is a cross-over study without wash-out periods. Hall is (or at least was) the principal investigator. In December he presented interim results in London, prompting the recent flurry of media attention that I wrote about in January.

That study randomizes subjects to eat four different diets for only one week each. No wash-out periods. When Hall reported on the preliminary results—"Now, the drum roll," he told his London audience—he had data from 18 of 36 subjects.

If Ludwig, Willett and Putt are right, that trial has already failed. Its design—one week diet periods, no wash-out periods—had pre-ordained it.

Then there's the Nutrition for Precision Health initiative, the $170 million future of NIH nutrition research (at least pending any MAHA restructuring).

The NfPH was launched with the exceedingly ambitious goal of providing us all with AI-guided, personalized dietary advice. "Nutrition", says the NfPH website, "is not one-size-fits-all." Hence, the goal of the study:

The Nutrition for Precision Health study is researching how nutrition can be tailored to each person's genes, culture, and environment to improve health.

Fourteen centers will recruit 8000 participants studying how they respond to a trio of dietary interventions. Those data will then be fed into the AI-developed algorithms which will take it from there.

This study, too, uses metabolic wards and cross-over designs, but includes wash-out periods of “at least 14 days”, which may (or may not) be sufficient. But the subjects will eat the diets for only only two weeks—far too short to extrapolate to longterm health effects of the kind we want to know when discussing chronic diseases and providing diet advice.

Ultimately the study seems to depend on AI being smart enough that the "AI-developed algorithms" will be able to extrapolate from two weeks on a diet to longterm health and disease outcomes. I don't see how it's possible, but I'm not an AI.

Not that the reporters on the nutrition beat covered them, as I discussed.

The plant-based vs animal-based nature of the diets was window dressing.

The title of the paper: “Diet order affects energy balance in randomized crossover feeding studies that vary in macronutrients but not ultra-processing…” [my italics]

Conspicuously absent from Hall’s speculations were the kind of hormonal-metabolic phenomena that were built into the carbohydrate-insulin model and that Ludwig had already cited as reason why Hall’s two week studies were too short.

Thanks again Gary for the reporting. As a layman, this whole thing is absurd. That Hall takes such umbrage in public and resigning in protest is likewise absurd. For God's sake, if we're going to spend millions of taxpayer dollars, get the study design correct at the outset, or don't spend the money.

You write so clearly that your criticisms of Hall seem intuitively obvious, and that makes me wonder how a respected researcher like Hall could fail to detect and neutralize such obvious errors early in the planning of his research. I guess there is enough funding only for flawed research?