Tales from the History of Carnivore Diets

Nutrition dogma habitually ignores the past. Paying attention, after all, can be terribly inconvenient.

…students sometimes comment that because of the enormous amount of current knowledge they have to absorb, they have no time to read about the history of their field. But a knowledge of the historical development of a subject is often essential for a full understanding of its present-day situation. Hans Krebs, 1981

Okay, so let’s talk about history. This will be a new feature in Uncertainty Principles, something I hope to do every few weeks.

As those who have read my books know, I fell down a rabbit hole when I started researching the history of nutrition dogma back in the late 1990s. Beginning with a series of investigations for the journal Science, I asked, in effect, the simple questions that every journalist and researcher should ask of propositions that are taken as articles of faith: why do we believe they’re true? On what evidence are they based?

This is why articles in the medical literature or serious non-fiction books include notes and references. That allows the reader to answer those questions. My profession evolved from investigative journalist into historian of medical science because of this process of following the references/citations back in time. I was looking for the point at which speculative propositions transformed from hypotheses to dogma. I wanted to know whether the evidence justified the transformation. I had no idea how far back in time I had to go. As it turned out, it’s quite a journey.

In my most recent book Rethinking Diabetes, I began the epilogue with a discussion of the history of the field of Evidence-Based Medicine. I did so, because that discipline essentially began with a handful of physicians trying to answer similar questions with the same process. I quoted David Eddy, a pioneer of the discipline, saying that he had come to realize through his research that “medical decision making was not built on a bedrock of evidence or formal analysis, but was standing on Jell- O.”

There’s no understanding the current belief system, as Krebs said, without understanding how we got here and on the basis of what evidence.

The history I’ll include in these posts will typically be of two sorts. 1). Excerpts from the medical literature on the early research/thinking on obesity and nutrition. This will be the subject of my next book and there’s plenty to share. 2). Reports I find fascinating, typically because they make observations that stand in opposition to conventional nutrition or obesity dogma today.

It’s always possible, of course, that these observations are completely unreliable—the equivalent of eye-witness testimony on unidentified flying objects—but it’s also possible that they’re not.

This week, for instance, I have three observations about carnivore or mostly carnivore diets: one from an Italian physician in 1886 using the carnivore diet as a treatment for obesity; two from Americans living off the land, half a century earlier.

Keto and carnivore as observations that challenge nutritional wisdom

Most of the discourse on social and traditional media about keto and carnivore diets is about their long-term health consequences and whether or not they’re easy to follow.

What we rarely see discussed, though, is what keto and carnivore tell us about the relevant nutrition science.1

Nutritionists have a collection of beliefs, some of them a century old, that were never well-tested (i.e., standing on Jell-O) and that the evidence from these diets now seem to contradict. And weirdly enough, the evidence always did.

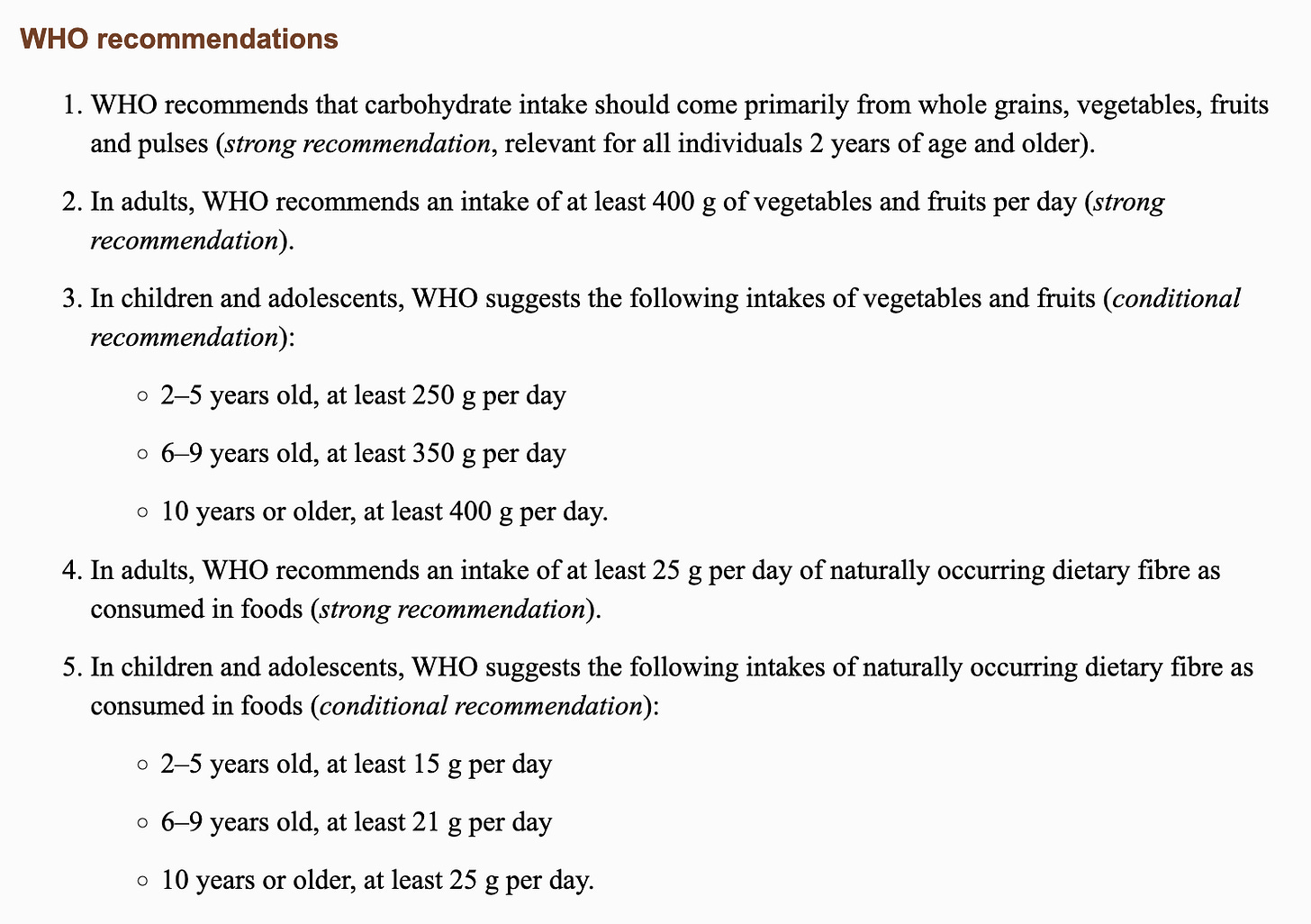

To put these historical accounts in this scientific context, it helps to know precisely what’s recommended today for the necessary plant-based content of a healthy diet. Here, for instance, is the World Health Organization’s recommendations for carbohydrate intake in a healthy diet:

Nutritionists will say we need a minimum of 130 grams of dietary carbohydrates daily because the brain uses glucose as a primary energy source (or at least it does when were eating a carb-rich diet) and this is roughly the amount of glucose it burns through each day. We need fiber, of course, for a healthy gut biome and, if nothing else, to avoid constipation. And we need fruits and vegetables, ideally fresh, for the vitamins and anti-oxidants they contain. These, in turn, will prevent deficiency diseases—scurvy, most conspicuously, which is believed to develop over the course of weeks to months in a vitamin-C deficient diet. (See, for instance, ChatGPT’s answer to the question: “What happens to people if they consume a diet without any fruits and vegetables, not even fruit juice, and don't take vitamin supplements?”)

And yet, clearly people have been thriving on meat-rich, if not carnivore diets absent fruits, vegetables (grains, whole or otherwise) and legumes throughout history.

The Ashley-Smith explorations: Years of thriving on fresh meat alone

This first excerpt was recently sent to me by a historian friend who is finishing up a book on the history of the American West. It’s a paragraph from a book published in 1917 describing the experience of a crew of explorers led by General William Ashley and (later) Jedediah Smith. Known as Ashley’s hundred, they explored the American frontier from the Mississippi River to California in the 1820s. You can read about the explorations in Smith’s entry in Wikipedia.

This excerpt comes from Ashley’s own account, which is reprinted in the book:

In relation to the subsistence of men and horses, I will remark that nothing now is actually necessary for the support of men in the wilderness than a plentiful supply of good fresh meat . It is all that our mountaineers ever require or even seem to wish. They prefer the meat of the buffaloe [sic] to that of any other animal, and the circumstance of the uninterrupted health of these people who generally eat unreasonable quantities of meat at their meals, proves it to be the most wholesome and best adapted food to the constitution of man. In the different concerns which I have had in the Indian Country, where not less than one hundred men have been annually employed for the last four years and subsist altogether upon meat, I have not known at any time a single instance of bilious fever among them or any other disease prevalent in the settled parts of our country, except a few instances (and but very few) of slight fevers produced by colds or rheumatic affections, contracted while in the discharge of guard duty on cold and inclement nights. Nor have we in the whole four years lost a single man by death except those who came to their end prematurely by being either shot or drowned .

This reminded me of Richard Henry Dana Jr.’s experience on the California coast in the mid-1830s, or just a half dozen years later. Dana was a well-to-do Bostonian who dropped out of Harvard in 1831 and took the opportunity to experience the life of a common sailer. He signed up on a sailing ship, the Pilgrim, which would take him from Boston, around Cape Horn, to California to trade for cattle hides.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Uncertainty Principles to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.