Life Lessons from the Blue Zones? Maybe Not.

After a lengthy run of wonderful publicity from the media, Dan Buettner and his blue zones run into a storm of criticism. A good thing? Yes, but it misses the point.

“What if I said I could add up to 10 years to your life? A long healthy life is no accident. It begins with good genes, but it also depends on good habits.” Dan Buettner, The Secrets of Long Life, National Geographic, November 2005

Some ideas just seem obvious, or at least they do after someone else thinks them up: Find the places in the world, however remote, where humans seem to live the longest and healthiest lives; identify what dietary and lifestyle habits these populations all seem to share and then suggest to the rest of us that we eat and live as they do.

If you have respected organizations like National Geographic and the National Institute of Aging helping to fund the research; if your lessons are in line with conventional thinking, and if you can publicize them in a National Geographic cover article headlined “The Secrets of Living Longer,” you can create a nutrition and wellness empire promising to “transform your community, your worksite, your life”, generate thousands if not tens of thousands of news articles promoting your ideas far and wide, and garner almost universal acceptance.

If one of the lessons is plant-based eating, all the better, because the advocates of plant-based eating are likely to accept your research conclusions without thinking twice and disseminate it widely, if not zealously, as well.

So it is that the concept/social-phenomenon/business-enterprise of the blue zones exploded onto the nutrition scene in 2005 and thrived, unfettered until very recently by the kind of critical response that is, regrettably, an essential characteristic of a functional science.

Now the tide has finally turned, and the media has decided that’s newsworthy also. After those thousands to tens of thousands of articles promoting and disseminating the blue zone concept and lessons (“a mix of journalism, academic epidemiology, advocacy, and entrepreneurship delivered in easy-to-implement bullet points,” as The Atlantic described them), the media has started doing its job of critiquing the research.

If we were tracing the spread of this critical journalistic thinking like a virus, it seems to have emerged in Australia in 2021 (The Sydney Morning Herald), found its way to London and The Economist in 2023 (archived here), and then to the U.S. last June, discussed in an episode of Freakonomics Radio. The New York Times caught up to the story in October, followed by Science in November (a history of the blue zones phenomenon and by far the best of these articles), and Fortune in December. It may have reached its apex two weeks ago with a lengthy guest essay in The New York Times headlined “Sorry, No Secret to Life is Going to Make you Live to 110.”

The author of that Times essay was Saul Newman, an Australian researcher working out of University College London. His essay was a lay version of an ever-evolving preprint that he first posted online in 2019. It had yet to be published or peer-reviewed. Now it was a story regardless.

Newman’s training, according to the UCL website, was in medical science, plant science, and genomics before he moved on to demography and single-handedly prompted the recent outbreak of critical journalism.

Newman’s point, and that of all these articles, is that many of the centenarians and nonagenarians in these blue zones were almost assuredly not as old as they claimed. His Times essay pulled no punches, ending with the declaration that “the science of extreme longevity continues as an immense joke.”

Of course, I might say the same thing about nutrition science in general and nutritional epidemiology in particular (and I have in slightly less inflammatory language). But Newman wasn’t critiquing the nutrition implications. He was only critiquing the blue zone basis for them: Are these remarkably healthy, very-senior citizens quite as senior as they say?

The media has followed along, giving us a refreshing dose of critical thinking that nonetheless misses, if not one critical point, then the critical point, which I’ll discuss (spoiler alert: it’s the association-implies-causality issue).

How it all begins

The blue zone concept itself was apparently Dan Buettner’s idea1, and it would make Buettner famous. In 2000, Buettner was the holder of several records for long-distance cycling, a journalist, and something of an adventure specialist when he “launched a program aimed at identifying all of the world’s longest-lived people and identifying their common denominators.” Acoording to Science, “he was running an online educational project on the world’s scientific mysteries when the Japanese government invited him to visit Okinawa, home to about 1.3 million people. Officials wanted to know why the island’s population appeared to be living longer than any other on the planet.” Buettner did, too. From that beginning, Buettner would go onto become a National Geographic Explorer and Fellow, and National Geographic, the magazine, would create a cottage industry publicizing his adventures, research, thinking and life lessons.

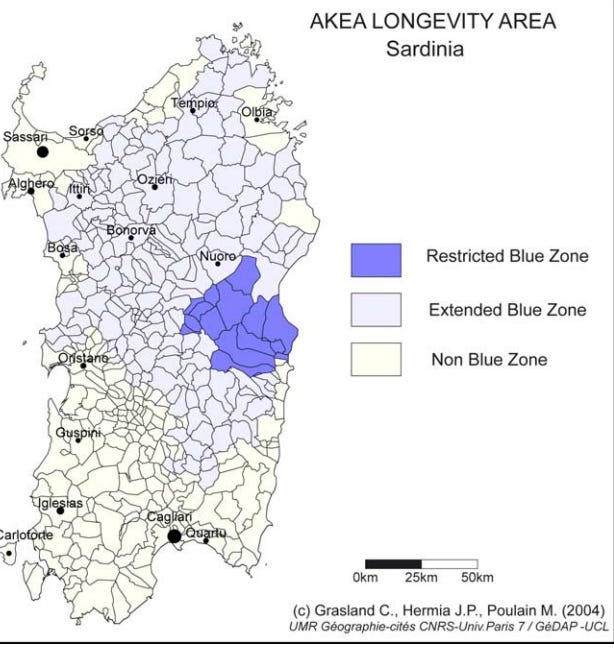

It wasn’t Buettner, though, who first evoked the term blue zone publicly to describe what was then known more commonly and descriptively as a longevity hotspot. That was Giovanni Mario Pes, an Italian Medical statistician, and Michael Poulain, a Belgian demographer, and their academic co-authors in a 2004 paper identifying a single remote, mountainous region of Sardinia as “a geographic area characterized by extreme longevity.”

By then Pes and Poulain were apparently already collaborating with Buettner on the blue zones project.2 The timing is unclear, but Buettner, Pes and Poulain may have already founded what would become their burgeoning health and wellness company—Blue Zones, “dedicated to creating healthy communities across the United States”—-and trademarked the blue zone term. The company website describes blue zones as both “a brand and a certification mark.” Only the company itself can designate whether a community deserves to be called a blue zone.

In 2005, Buettner turned the Pes, Poulain et al. observations about Sardinia into that National Geographic cover story, adding Okinawa in Japan and the Seventh-day Adventists of Loma Linda, California to the blue zone list. Buettner’s contribution to the research appears to be the life lessons culled from the blue zones. Over the next three years, Poulain, Pes, and Buettner sifted through potential blue zones, rejected some as unverifiable (Crete, for instance), and added the Nicoya peninsula in Costa Rica and the Greek island of Ikaria to the list: now five, in total.

Buettner published the first of his numerous best-sellers on the blue zone research in 2008—The Blue Zones, Lessons for living longer from the people who’ve lived the longest . (“A must-read if you want to stay young!” says Dr. Mehmet Oz, who may be running the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services by the time you read this.) By 2010 Buettner had begun to expand his focus from longevity to happiness, with yet another best-seller, Thrive: Finding Happiness The Blue Zones Way. (”A must-read for living happier,” says Dr. Oz.) Buettner’s pursuit of happiness research would become another National Geographic cover in 2017, documenting the lessons to be learned from the “most joyful places on the planet.” Now it was Costa Rica, Denmark and Singapore that were telling us not how to live long lives, as the blue zones did, but how to live happy ones.

In 2020, Buettner sold the company to Adventist Health, which describes itself as “a faith-based, nonprofit, integrated health system” and is affiliated with the Seventh-day Adventist Church. And for those who hadn’t read the books or simply wanted more of the blue zones, Buettner produced and starred in a 2023 Netflix limited series, Live to 100: Secrets of the Blue Zones.

Lessons for longevity; criticisms of the research

All of this was possible, perhaps, because of the nine lessons that Buettner had gleaned from his observations, the “common denominators” as the Blue Zones website says. From the original National Geographic article: honor family, drink red wine, stay active, find purpose, keep friends, eat vegetables, have faith (a lesson then from the Seventh-day Adventists blue zone community in Loma Linda California), take time off, and celebrate life.

As with the USDA Dietary Guidelines, as I described in a recent post, the blue zones advice to eat vegetables has transformed over the years into advice to avoid meat. The Blue Zone website dietary advice now tells us (in the language of the website) to retreat from meat, go easy on fish, reduce dairy, eliminate eggs, slash sugar, drink water (no longer red wine, as the nutrition community has begun to challenge the health benefits of even moderate alcohol consumption) and incorporate a daily dose of beans.

More generally, it says, in capitals, “SEE THAT YOUR DIET IS 95-100 PERCENT PLANT-BASED,” which is hard to equate with the original blue zone research.

If nothing else, the Sardinians consumed considerable dairy—pecorino cheese, specifically—and the Ikarians ate their fair share of fish, meat and cheese. “The people of Ikaria,” as the island’s website reports, “still base much of their diet on wild greens, beans, fruits and vegetables picked in season, fish just plucked from the sea, pigs raised in the backyard, goats that graze wild in the mountains, and chickens that also eat leftovers from family meals. Family and locally produced olive oil, honey, wine, goat’s milk and cheese and mountain teas are all used and consumed in abundance.”

The Blue Zone dietary advice is, however, closely aligned with the dietary precepts of the Seventh-day Adventists.

One way or the other, no conventional wisdom was being challenged with these blue zone bromides—“sort of like standard public health promotion 101,” as one “expert on evidence-based public health” told Science— which probably explains why no criticism was forthcoming.

That began to change in 2019, when Newman first circulated his preprint making the argument that the extraordinary number of long-lived people in these blue zones didn’t just associate with the factors Buettner and his colleagues were promoting as life lessons—vegetable intake, strong social connections, etc.—but the “absence of vital registration,” as well.

Only 18% of ‘exhaustively’ validated supercentenarians [folks over 110] have a birth certificate, falling to zero percent in the USA, and supercentenarian birthdates are concentrated on days divisible by five: a pattern indicative of widespread fraud and error. Finally, the designated ‘blue zones’ of Sardinia, Okinawa, and Ikaria corresponded to regions with low incomes, low literacy, high crime rate and short life expectancy relative to their national average. As such, relative poverty and short lifespan constitute unexpected predictors of centenarian and supercentenarian status and support a primary role of fraud and error in generating remarkable human age records.

Other demographers had made these kinds of arguments in the past about longevity hotspots. Pes, Poulain, and their co-authors raised the issue in their 2004 paper: Their findings about Sardinia’s longevity hotspot, they wrote, “were remarkable but also suspicious [my italics] since all previous reports on exceptional long living populations concentrated in specific geographical areas have later been invalidated and explained by age misreporting or other errors in data collection.”

The most notorious example would come in 2010, when the Japanese government did an audit of the nation’s centenarian population and realized that some 230,000, 82% of them, were missing, likely long dead, whose centenarian status would be the result of clerical errors or fraud. As the BBC reported at the time:

The inquiry followed the discovery of the mummified remains of Sogen Kato, who was thought to be the oldest man in Tokyo.

However, when officials went to congratulate him on his 111th birthday, they found his 30-year-old remains, raising concerns that the welfare system is being exploited by dishonest relatives.

Reports said he had received about 9.5m yen ($109,000; £70,000) in pension payments since his wife's death six years ago, and some of the money had been withdrawn.

That story got considerable play in the media, if nothing else, I suspect, because it’s nice to know the Japanese are not quite so much healthier as a society than we are, and many of us love a good fraud story. “Some families,” as The Guardian reported, “are deliberately hiding the deaths of elderly relatives in order to claim their pensions.”

But the commercial blue zone phenomenon was just getting started in those days. The more general critiques of longevity research or of the vital records data from specific hotspots generated little interest outside of the demographers themselves. It took the success of the blue zone concept and the thriving business it had become to turn the critiques into a good story.

Eventually, Newman’s preprint started being noticed and journalists began warming to the story, happy to bet that Newman was right and that Buettner and his colleagues were peddling bad science. When The Economist ran with the story in 2023, the article appeared with a graphic detail described as “olive oil and snake oil.” Perhaps for legal reasons, the words blue zones went unmentioned. When Freakonomics Radio ran its episode last June, the London-based “reformed journalist” who was discussing Newman’s still-unpublished preprint, called it “an extraordinary document. He just tears the entire thing [i.e. the blue zones concept] to pieces from beginning to end.”

Newman did the same two weeks ago in his New York Times essay:

The longstanding concept of blue zones suggests that people reach age 100 in these areas by doing small amounts of exercise, eating mild vegetarian diets in moderation, attending religious services and living with family as they drink and socialize with friends. Yet independent data reveals otherwise.

Okinawa is the hallmark case. Okinawans are overwhelmingly atheist, have extremely high rates of divorce and have double the poverty rate of the national average. In government surveys, Okinawans ate copious quantities of meat for decades and had the highest male body mass index since 1975 compared with other prefectures. Two demographers involved in blue zone research even acknowledged that Okinawa’s mortality rate now is unremarkable. While they cite generational differences to explain this fact, they admit there could have been flaws in the initial reports of extreme longevity. I find that explanation quite likely.

But revealing these patterns has not led to a broad reckoning in longevity science. Too often demographers have doubled down, and the goal posts have been carefully moved. The blue zone popularizer Dan Buettner admitted how he discovered Loma Linda: not by examination of global survival data but because his National Geographic editor told him, “You need to find America’s blue zone.” He has also talked about Singapore as a sixth blue zone, even though a former collaborator of his has expressed skepticism. The Okinawan, Sardinian and Costa Rican blue zones simply shifted or disappeared when the data and criticism arrived.

The absence of what Newman calls “a broad reckoning” in longevity research is a recurring theme in all research having to do with chronic disease epidemiology and nutrition. I’ll discuss this again in (probably many) future posts. If we’re lucky we get a thoughtful response to the criticism from the researchers, who should be thankful for the criticism. (Whether all of it is correct, some of it is likely to be, and the researchers can learn from that.)

If not, we get crickets, the researchers valuing public relations over good science, and deciding that the most productive approach, at least for their careers and funding, is to ignore the criticism. They’ll assume the bad attention will fade with the next news cycle or be buried under the tens, hundreds or perhaps even thousands of vaguely relevant journal articles that are already in the works, perhaps already accepted by the journals, and that will be published in the coming months with no awareness of the criticisms, however valid they might be. (Another problem I’ll discuss in future posts.)

In this case, Buettner responded to Newman’s claims—here, for instance—and his academic collaborators did so in a letter on Buettner’s website here. They point out that Newman was a plant biologist “with no academic training or expertise in demography, gerontology, or geriatrics, and has no record of publication in these fields of study.” Then they argue that Newman’s critique might relate to longevity research in general but they had taken all this into account already. Hence, it wasn’t relevant to their work.

Newman’s draft papers, which he is vigorously promoting in the mainstream media, attempt to discredit the blue zones by presenting a series of false equivalencies. He argues that the excessive number of centenarians and supercentenarians in non-blue zone areas is due to poor demographic records, which is often the case. However, he ignores the fact that this criticism does not apply to blue zones, where ages have been rigorously validated with modern, accurate demographic methodology.

Newman also alleges that birthdates in blue zones exhibit “age heaping” patterns. However, such patterns do not appear in the validated datasets from blue zones, which show no unusual distribution of birthdates. Furthermore, his examples of fraudulent death registrations in Japan and the U.S. have no bearing on blue zones, as we have meticulously validated all ages before analysis, expunging any such cases from our datasets.

Newman’s response, in The Sydney Morning Herald article, is priceless, although he sacrifices the science more than I’d prefer for a clever retort: The response from Buettner’s collaborators, he says, “was basically what you’d expect if you told the yeti-hunting society that yetis did not exist.”

As for why his preprint remains unpublished, “since then,” he says, “it’s like I’ve been trying to publish the findings that yetis don’t exist in yeti-hunting journals. That’s been, let’s say, an experience.”

This leaves the validity of the blue zones themselves as one of the many he-said-she-said stories in modern science. Without access to the data and perhaps years of training in demographic research, it’s difficult, if not impossible, to know who to believe. Both sides have profound conflicts of interest: cognitive and financial for Buettner and his collaborators; cognitive and maybe career conflicts for Newman.

The longevity researchers are likely to side with Newman, but the blue zones have never been core to their work. “It’s not a study; it’s an observation,” as the New York Times quoted Nir Barzilai, director of the Institute for Aging Research at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, “It’s an observation which is consistent with what we think we know about aging. But it’s not a science.”

Because it’s consistent with what the nutritionists think they know, however, I’m betting the nutrition community pays little attention. I wouldn’t be surprised if they continue to refer to the blue zones and the accompanying dietary lessons when convenient without bothering to mention that it’s all been called into question.

How about science lessons from the blue zones?

Ultimately the blue zones raise two critical issues.

First is the obvious one: Once a proposition becomes a money-making venture, can we trust the proponents to do rigorous science, which might, as a result, kill their money-making venture?

Any of us who have written books arguing directly or indirectly for a particular dietary philosophy are open to this accusation, and those who want to believe that venality invariably triumphs over intellectual integrity will do so even in the absence of any meaningful evidence. (In this enterprise, association is always assumed to be causality by those whose preconceptions could benefit from the assumption.)

Start a company to sell products based on your interpretation of the research and the conflict becomes that much more concrete. If the blue zones research falls apart, which may already be the case, I don’t expect that Buettner or the Blue Zone organization will readily acknowledge it. This is an occupational hazard in this business. There’s no getting around it.

Second, as Barzilai was quoted saying, the blue zones are an observation not a study, by which I assume he means an experiment. Even if Newman is wrong and the blue zone populations are or at least were the longest-lived populations on Earth, what they provide is an association between lifestyle, diet and longevity without causal information. They tell us that the long-lived people in these populations had a sense of community, friends, family, purpose, and that they ate their vegetables, not that any of these things made them live longer than they might have otherwise.

Now we’re back to the familiar story: whether a plant-based diet—either avoiding meat or getting 90 to 95% of calories from plant sources—is in part responsible for the longevity in these blue zone populations.3

Buettner and his colleagues are assuming that the way these people eat when they were studied was a reason (one of 9) that they were so seemingly long-lived, specifically the plant-rich nature of their diet. But we don’t know that.

Assuming diet played a role, it could have been what they were eating when they were younger.4 It could have even been what their mothers were eating when they were in the womb. It could have been the response to the food shortages that followed the devastation of World War 2 in the Mediterranean islands and certainly on Okinawa.

And, of course, it could have been what they were not eating. Buettner, a vegetarian, implies the latter by suggesting the mostly plant diet, the relative absence of red and processed meat, as a health lesson to be learned.

Buettner includes the avoidance of processed food as a dietary precept in part because of a conversation he and I had back in 2012 when he was finishing up his New York Times Magazine article. The Times editors had suggested he talk to me because they had published an article of mine—“Is Sugar Toxic”-- a year earlier. That article had touched on the observation that diabetes and related chronic diseases were rare in populations that ate little sugar, and the absence of sugar might have been the reason why (as I later argued in my book, The Case Against Sugar).

Buettner understood the point, and he added this paragraph to the article:

Of course, it may not be only what they’re eating; it may also be what they’re not eating. “Are they doing something positive, or is it the absence of something negative?” Gary Taubes asked when I described to him the Ikarians’ longevity and their diet. Taubes is a founder of the nonprofit Nutrition Science Initiative and the author of “Why We Get Fat” (and has written several articles for this magazine). “One explanation why they live so long is they eat a plant-based diet. Or it could be the absence of sugar and white flour. From what I know of the Greek diet, they eat very little refined sugar, and their breads have been traditionally made with stone-ground wheat.”

That no one had suggested this to Buettner or his colleagues for the better part of a decade was not a good sign.

Ultimately these blue zone observations are an extension of observations I’ve written about in all my books: the concept of nutrition transitions and the appearance of western diets and lifestyles in association with the increased prevalence of western chronic diseases; obesity, diabetes, CHD, etc.

The aged of Sardinia, Ikaria, Okinawa and Nicaragua had lived much of their lives (however long they might have been) with little access to western foods. (The Seventh-day Adventists avoided them on principle.) And they lived in areas of the world that had the kind of temperate climates that make living relatively easy. It’s possible that the primary lessons to be learned from these populations is to live in a temperate climate and avoid processed foods, specifically sugar and refined (i.e., white) flour. And this could explain why the longevity hotspots are now apparently evaporating, as western foods become ever more widely available.

As Science writes:

Yet even proponents of the blue zone concept concede that some of the regions may no longer be exceptional. Luis Rosero-Bixby, an emeritus demographer at the University of Costa Rica who helped declare the blue zone in Nicoya in 2007, recently published a study showing people born after 1930 are no longer living unusually long lives. The same is true on Okinawa, according to a paper published by Poulain this year.

Even in the very first blue zone, in eastern Sardinia, some municipalities no longer show exceptional longevity, Pes says, although others not included in the original survey do. Buettner and others blame the Western lifestyle, which is encroaching. As the traditional ways of life are lost, the reasoning goes, people exchange walking for driving, balanced diets for ultraprocessed food, and old rural communities for life in cities.

So maybe the key is the absence of western foods and the mostly-plants are just a coincidence. Had these populations eaten more animal products, they might have been even healthier than they are. There’s no way to know.

We’re back to the familiar story: something about western, industrialized diets is bad for our health. No surprise there. And we’re back to asking what that is. Refined grains and sugars remain a simple explanation because those are the foods that began appearing in populations in large quantities beginning in the 1800s with the industrial revolution, when diabetes rates in particular started to climb. Sugar and white flour were considered obvious suspects from the 1920s to the 1960s and 1970s when British researchers first introduced and then institutionalized this discussion of western diets and their harms. Maybe seed oils play a role. Maybe we just eat too much of these foods (which I doubt).

One thing is for sure, the blue zone research will not be able to tell us.

According to the website of the Blue Zone company that Buettner and his collaborators would launch.

The Blue Zone website says Buettner coined the blue zone term “during an exploratory project he led in 2004,” but the Pes, Poulain et al. paper does not mention Buettner’s name even as an acknowledgement.

I find it easy to believe that people with friends and family around them and a sense of community and maybe even faith might live longer because their lives are rewarding. They live longer, in effect, because they want to live longer. And I’m willing to believe that eating green vegetables is benign, if not beneficial, because my mother told me so.

As Poulain and his colleagues wrote in 2004 about Sardinia (with my italics), “For many years an agricultural economy, pastorizia [i.e., pastoral], and livestock breeding represented the only sources of income.”

I love when Gary weighs-in on a topic. Excellent work as always.

I read the Blue Zones book a couple years ago. I found it quite obvious that the author's conclusions do not actually follow from what he just observed throughout the book.

Italians eating vegan?! Are you kidding me? These people inhale fatty pork like nobody's business.

I get that having a sense of purpose & a community is nice, and maybe prolong your life. But none of the dietary choices seemed to be founded in anything but vegan ideology.