The BodyBuilder Bias, or Why Lean People Can Be Clueless about the Nature of Obesity

If you can eat carb-rich meals and stay lean, does that mean we all can?

My last post on the questionable expertise of podcasters—Derek Thompson and Andrew Huberman, specifically—presented an opportunity to discuss another of the cognitive biases that come up repeatedly in the nutrition and obesity world. (It also reminded me of quite how weird things can get on X, as we’ll see, when you’re challenging conventional wisdom on diet and disease.)

I’m going to call it the body-builder problem for reasons that will become clear, but it’s a cognitive bias that has haunted the sciences of nutrition and obesity for as long as folks have been speculating as to the connection. It affects virtually all those experts who are naturally lean, and I can think of no other way of misthinking that has done so much damage to the science and our understanding of why we get fat.

In that last post, I discussed the sources that Thompson and Huberman relied on to establish that they knew the boring truth about obesity, that those of us, they say, who struggle with our weight do so merely (ho hum!) because we eat too much. Huberman believed he knew this to be true because Layne Norton, PhD, had explained it to him on the HubermanLab podcast.

Norton has a Ph.D. in nutrition and he can discuss subjects like protein metabolism with admirable erudition. But he is also a bodybuilder and a very successful one and that’s given him a perspective that he thinks is relevant to obesity.

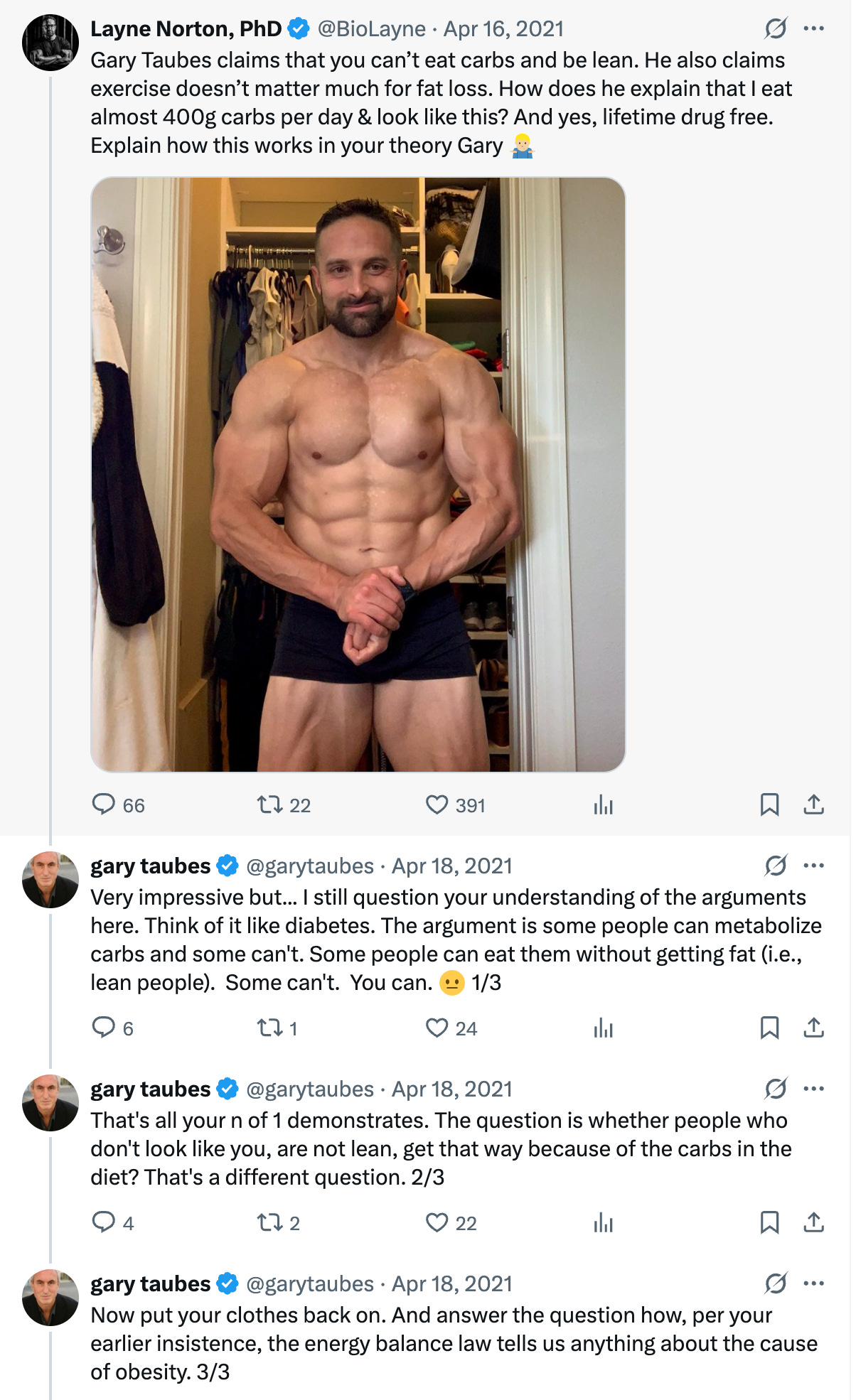

I should probably have admitted in that last post that I’ve had run-ins with Norton in the past. I interacted with him repeatedly on what was then still called Twitter. I eventually muted him1 after this exchange:

Norton chose not to respond to my last question about energy balance, which is when I muted him, although not why. I would have preferred to continue discussing the science and our points of disagreement. I’m averse, however, to having strangers (or friends, for that fact) sending me photos of how they look in their underwear, whether they’re trolling me, as Norton was, or not.

Norton’s question, nonetheless, is very much worth discussing. That he wants me to explain how he can eat 400 grams of carbohydrates and look like he does is a consequence of his perspective, his bias, and that bias is critical to understanding how we came to think about the dietary cause of obesity: the eat too much assumption. In short, if people didn’t naturally think the way Norton does we might have an entirely different theory of obesity.

Before getting into the cognitive bias, though, let me first clear up the straw man problem: “Gary Taubes,” Norton wrote, “claims that you can’t eat carbs and be lean.”

One way to think about this is via the lens of Occam’s razor, which is translated from the Latin as “Entities must not be multiplied beyond necessity.” By the word “entities,” think hypotheses or explanations. Occam’s razor suggests that we should not invoke a complicated hypothesis to explain observations, if a simple hypothesis will suffice. When scientists talk about a parsimonious hypothesis, they’re paying homage to the the logic of Occam’s razor. It’s been a foundational principle of good science for hundreds of years, just as it is for any endeavor that involves solving a problem or explaining the unknown.

The operative words, though, in Occam’s razor are “beyond necessity” or, in my version of it, “if a simple hypothesis will suffice.”

When the phenomena were trying to understand cannot be explained by a simple, or the simplest possible hypothesis, then complications become necessary. We may eventually conclude that the hypothesis is far more likely to be wrong than right, that it accumulates too many complications and still fails to explain the observations. Or we may conclude that another, simpler hypothesis does a better job of explaining the observations. If not, we may settle on the level of complication that does the job.

That’s how the process of science works or at least is supposed to work.

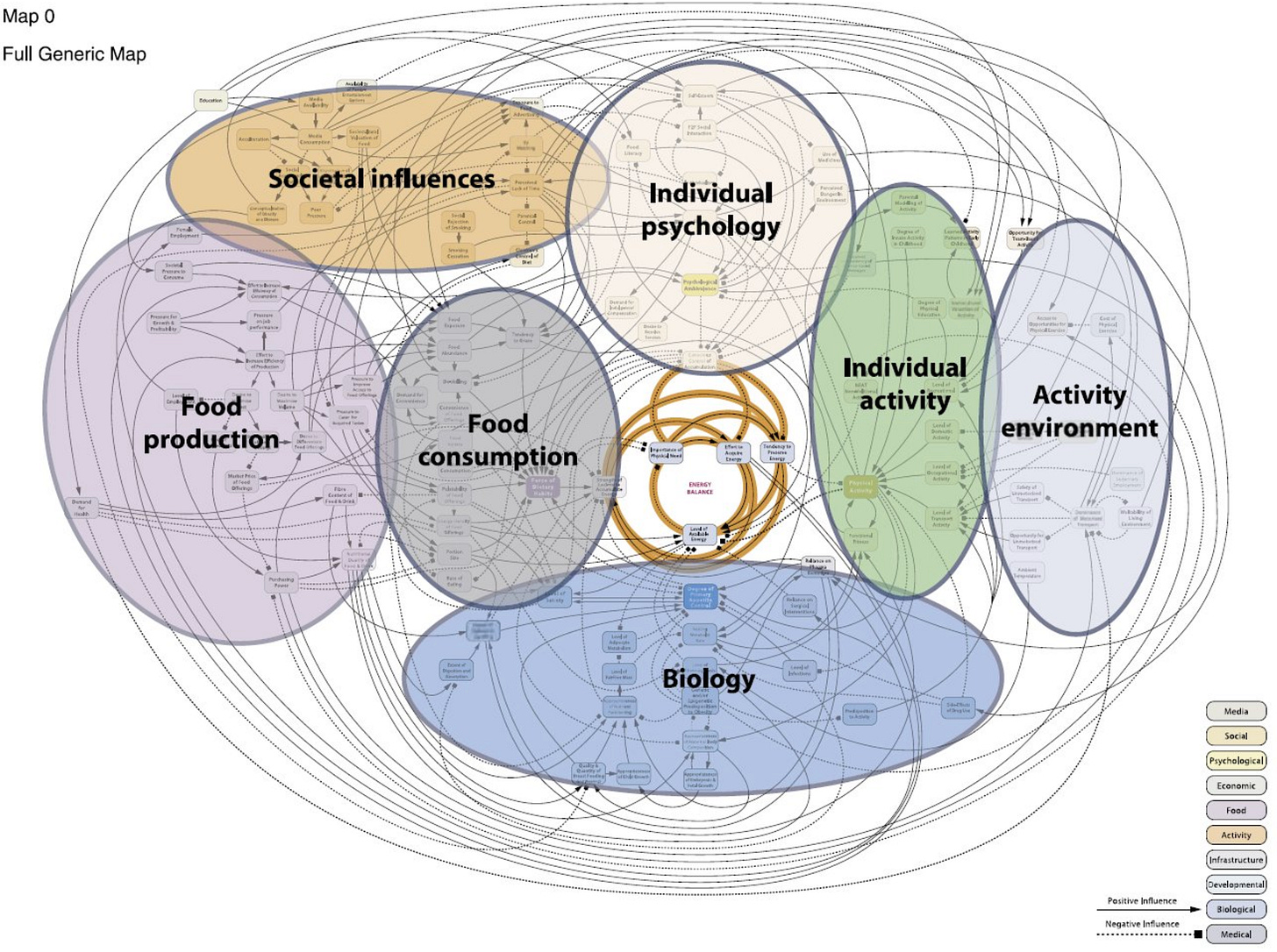

One of my critiques about obesity research in general is that once the researchers found that their belief system (the “boring truth” that we get fat because we eat too much) didn’t solve the problem of human obesity (that obese people who tried to eat less didn’t reverse their condition) or prevent the obesity epidemic from continuing to get worse, they were happy to multiply entities endlessly. The one thing they didn’t do was consider the possibility that their simple hypothesis was the wrong hypothesis. This multiplication of entities process gave virtually everyone in the field something to study, but did so without ever making meaningful progress on the simplest possible question, which is why people with obesity have such trouble maintaining a healthy weight.

Instead, we ended up with a hypothesis that looked like this (h/t to the British exercise physiologist Samuele Mercora who shared this image in the discussion that followed the Norton tweet):

Norton’s misstatement of my thinking, his strawman, can be seen as the simplest possible carbohydrate-obesity hypothesis: all carbohydrates are fattening to all people and so “Taubes claims you can’t eat carbs and be lean.”

But I don’t. And I don’t because the proposition is absurd. Clearly the world is full of people who eat carbs and are lean, albeit a smaller proportion of the total planet’s population now than ever before.

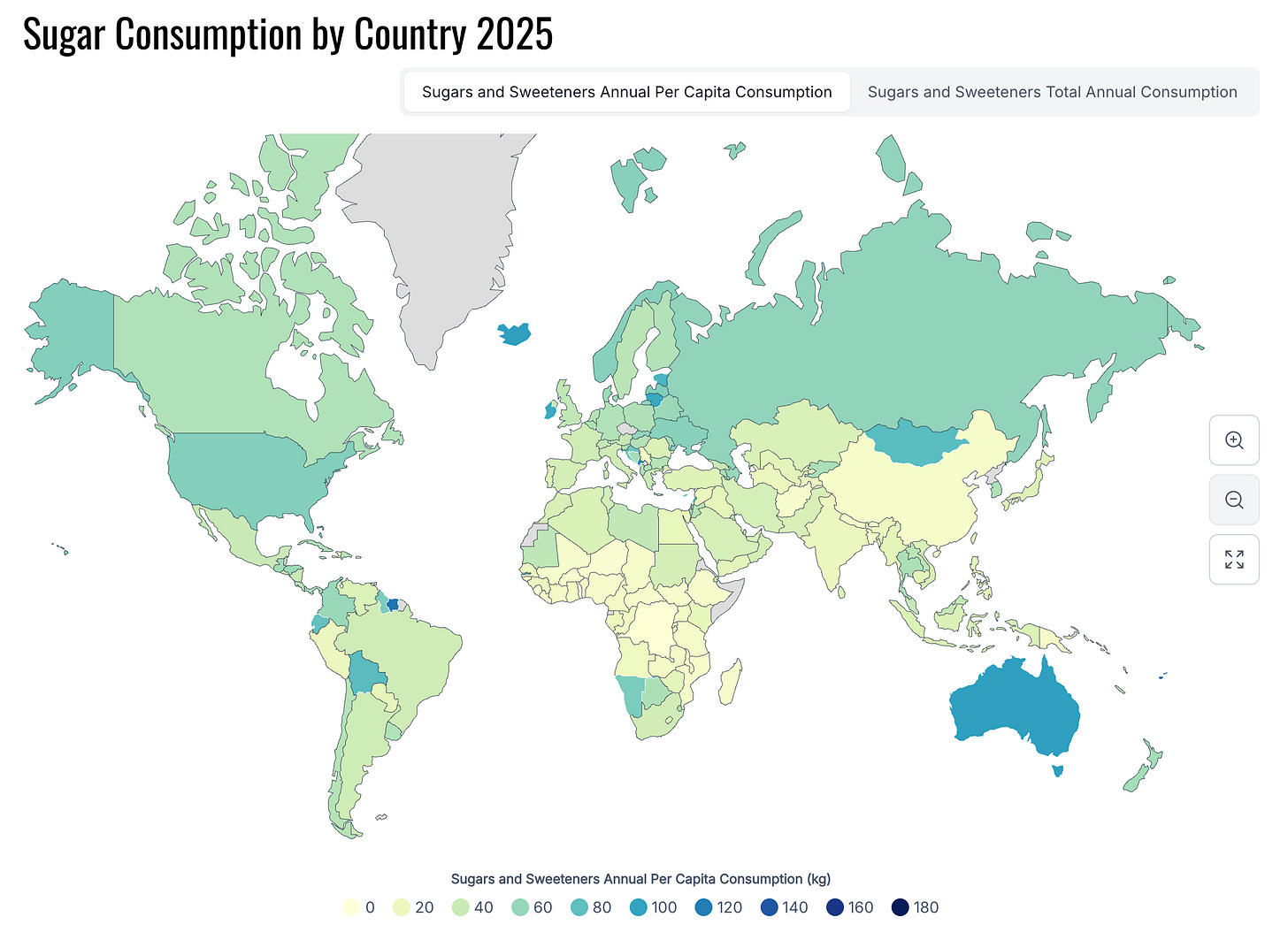

The populations of South and East Asia, for instance, have always been the conspicuous counter-argument to the simple proposition that all carbohydrates are fattening. That one to a few billion people (depending on era) remained lean and apparently healthy on carbohydrate-rich diets and even high-glycemic index, and so easily digestible carbohydrate-rich diets (rice and wheat) requires explaining by any viable theory of diet-induced obesity. By necessity, the leanness of these few billion South and East Asians has to be explained also. The simplest possible hypothesis is clearly wrong because it can’t do it.

When I first started doing research on this subject 25 years ago, this was an issue I raised in one of my earliest interviews, with an epidemiologist/biostatistician then working at the Harvard School of Public Health who had been born and did his undergraduate education in China. If high-glycemic index carbohydrates are fattening, I asked him, how do we explain the lean carb-eating people of China and the other nations in the region. “They’re peasants,” he told me, by which he meant that the individuals in those populations that got most of their calories from rice and wheat were both relatively poor and very hard-working.

I still hear variations on this logic from academics who mostly think like I do about the cause of obesity. Carb-rich diets can be benign, by this logic, even when the carbs are mostly high-glycemic grains like rice and wheat, if getting your minimal caloric requirements requires a hard days work in the fields to do so.

The South and East Asia experience is one of many reasons why the hypothesis discussed in my books is that refined carbohydrates and sugars are deleterious, not carbohydrates per se. 2 If Layne Norton had wanted to be vaguely accurate (and maybe if Twitter didn’t have a 280-character limit), he would have started with the strawman that I claim you can’t eat refined carbohydrates and sugars and remain lean, but even that’s absurd.

The fact that South and East Asians consumed plenty of refined carbohydrates is one reason why I present the evidence for sugars alone (sucrose and high fructose syrups) in my book The Case Against Sugar. In that book, I’m suggesting that these Asian populations have remained relatively lean and healthy on their carb-rich diets, even high-GI carb-rich diets, because those diets were always relatively sugar-poor and mostly still are.

Sugar, sucrose, is a molecule of glucose bonded to a molecule of fructose, and what I propose in The Case Against Sugar (and Robert Lustig and Richard Johnson have also proposed with variations on the mechanisms involved) is that it’s not the glycemic index that’s the problem—the speed of digestion of the glucose—but the fructose, most of which is metabolized in the small intestine and then the liver. 3

These Asian popluations, by this logic, are decades behind us in their obesity and diabetes epidemics because they’re decades or more behind us in their sugar consumption. By evoking the fructose-liver-metabolism mechanism, I am complicating the carbohydrate-insulin hypothesis in a way that I think can explain the relative leanness of these Asian populations. Am I right? Who knows?

There’s another complication, as well: timing is crucial in this argument because once these epidemics start, the predisposition to develop insulin resistance and to become obese and diabetic is then very likely passed on in the womb from mothers to children. This is a mechanism known as fetal-programming and it can increase the prevalence of obesity and diabetes from generation to generation. If you assume fetal-programming is at work in this epidemic, then reducing sugar consumption might have little effect on the epidemic itself.

The implication: what is necessary to launch these obesity and diabetes epidemics may not be necessary to keep them going. I discuss this in The Case Against Sugar , in the first of two “If/Then Problem” chapters, and I will discuss this in a future post.

Does being lean give you a valuable perspective on those who aren’t?

Returning to Layne Norton, PhD, and his simplest possible hypothesis/strawman, even in countries with a sedentary population and a sugar-rich diet—the United States, for instance—clearly an enormous number of people can tolerate these diets without getting obese.

The evidence: look around. We can assume that some huge proportion of the lean people are the ones who can tolerate eating carbs. So, yes, you can eat carbs and stay lean. Obviously. The world is full of people who do. Does that mean, though, that everyone can?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Uncertainty Principles to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.