Ultra-Processing Is the Bathwater. What About the Baby?

The recent obsession with ultra-processed foods spotlights a world of industry-related issues, while rendering sugar and refined grains almost benign in the process.

Questions of the day:

Calories or carbohydrates?

If carbohydrates, whole or processed (i.e., wheat berries or white flour)?

If processed carbohydrates, grains, and/or sugars? (i.e., glucose and/or fructose?)

Ok, I don’t expect answers to any of those questions. Still, in my science fantasies, I imagine that the nutrition research community would keep them in mind when doing their research, whether clinical trials/experiments or observational studies.

This is why I’m going to talk about calories, carbohydrates, and sugars, in a week when the headlines about the latest ultra-processed food (UPF) research include “Eating this diet can impact your performance in bed” (The Independent) and “Ultra-processed diet decreases male sex hormones, new study suggests.”

Mainstream nutritionists have traditionally acted as though these questions are not worth asking. Their recent embracing of the UPF concept can be seen as a license to do so in perpetuity. That latest clinical trial, what the Washington Post called “a small but rigorous study,” ostensibly about the effect of UPF on male reproductive health, happens to be another glaring example of the problem.

Before I get to that, though, as is my wont, first a digression into the context and the history here.

A 21st-century nutrition paradigm, for better or worse

In 2010, when the Brazilian epidemiologist Carlos Monteiro introduced elaborated on the concept of ultra-processed food in an obscure journal, World Nutrition (published by the equally obscure, then 2-year-old World Public Health Nutrition Organization), his stated goal was to replace the existing nutrition paradigm that focused on calories and nutrients as the primary variables.

The most important factor now, when considering food, nutrition and public health, is not nutrients, and is not foods, so much as what is done to foodstuffs and the nutrients originally contained in them, before they are purchased and consumed. That is to say, the big issue is food processing – or, to be more precise, the nature, extent and purpose of processing, and what happens to food and to us as a result of processing. Specifically, the public health issue is ‘ultra-processing’, as defined here.

Monteiro’s proposal ran alongside an editorial, apparently by the journalist-turned-public-health wonk Geoffrey Cannon, who summarized it this way:

He contrasts ultra-processed ‘type 3’ products, which are typically ‘fast’ or ‘convenience’ snacks and other items ready to eat or to heat, usually consumed by themselves, with ‘type 2’ processed ingredients. As he points out, these ingredients, like fats, sugars, starches and salt, are typically combined with ‘type 1’ fresh and minimally processed foods and drinks, and consumed as meals at or outside the home. What are most significant, he is saying, are not the chemical constituents of foods and drinks, but the products themselves – which are after all what we actually consume.If he is right, his thesis overturns conventional nutrition science, in as much as it is concerned with human health.

And then followed it up with the obvious question (with his emphasis):

What if he is right?

Now that Monteiro’s thinking has accomplished its objective, though, we owe it to ourselves to ask the other obvious question: what if he is wrong?

Or, rather, what if Monteiro’s approach to nutrition science, the rejection of the 20th Century reductionist focus on ”fats, sugars, starches and salt,” to be replaced by “the nature, extent and purpose of processing,” only leads further into the swamp of pseudoscience from which Monteiro, with his proposal, was hoping to lead nutritionists out?

Or what if he’s partially right? Another obvious question is, how would we know?

Let’s start with the bacon double cheeseburgers

Here’s a way to think of the question and the issues raised by the UPF concept: As Monteiro explained back in 2010, two iconic examples of ultra-processed foods “are ready-to-eat breakfast cereals and burgers.” A reasonable question to ask is whether these two foods are bad for us because they’re ultra-processed? And are they bad for us in the same way? Does that matter?

Reductionist nutrition science would have targeted the processing of the carbohydrates in the cereals (the glycemic index) and the sugar content. For the burger, it would have focused on the red meat and perhaps the saturated fat in the meat, plus the glycemic index of the bun, and maybe even the sugar content of the bun and whatever condiments were involved. Complicated stuff, but all implying a cause and a physiological, if hypothetical, harm.

Monteiro’s article began with a photo (below left) of a “mass-produced double cheese-and-bacon burger.” The problem with that burger, he implies, as with UPF in general, is that it was “made at a distance as separate items that are trucked in, assembled, and made ready-to-heat and –to-eat at a fast food site.”

But Robert Atkins, for what it’s worth, the eponymous creator of the Atkins Diet (a ketogenic diet) would have suggested the burger is benign if we eat only the bacon, cheese, and meat and leave the bun. Neal Barnard of the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine, advocates of vegan diets, would say the opposite: eat the bun, which is (mostly) benign, leave the animal products: the bacon, cheese, and meat.

As for me, I’m wondering if that same bacon cheeseburger becomes benign (absent the bun in my thinking) if I make it myself, in my kitchen, from locally sourced foods. Hence, if it’s not mass-produced, made at a distance, trucked in, and assembled at a fast food site (i.e., not the McDonald’s cheeseburger pictured below right) does that make it benign? And if so, why?

And, more importantly, how do we answer that question?

And, most importantly, should we not be asking these questions? Is that where nutrition and public health science have now settled?

In the reductionist paradigm that the UPF notion replaces, sugar or flour could be bad for our health for a host of reasons, and we can specify physiological mechanisms that might explain this.

Maybe refining speeds up digestion and absorption (the glycemic index concept); maybe it causes chronically elevated insulin (metabolic syndrome); maybe it depletes these foods of protein, vitamins, or other important constituents. Maybe, as with sugar, the only thing left is the energy, and so these foods can be justifiably condemned as empty calories (leading, by implication, to overconsumption). Maybe the fructose content (half of the sugar molecule) causes insulin resistance because it’s metabolized primarily in the liver? Myriads of such physiologic/mechanistic possibilities were on the table.

Now these foods—sugar and white flour, specifically—can be considered benign so long as they are not combined with other industrial ingredients into ultra-processed foods. In that case, it’s not the processing of the carbohydrates per se that causes harm—the metabolic effect of consuming these quickly digested and absorbed glucose and fructose molecules—but the involvement of the industrial additives, how far they’ve traveled to get to us, and perhaps even the intent of the industry that created them.

Here’s another way to think about it that makes it even easier. Below on the left is an 8-ounce glass of homemade lemonade. Ingredients: water, juice from homegrown lemons, and sugar. The three ingredients and the word “homemade” tell us this is not an ultra-processed food. Hence, benign. If we followed this popular recipe, it has 38 grams of sugar in it.1

On the right is an 8-ounce bottle of Sprite, a lemon lime soda. It has only 25 grams of sugar—a third less than the homemade lemonade. But the “sugar” is high fructose corn syrup, the water is carbonated, and the ingredients also include citric acid, “natural flavors,” sodium citrate, and sodium benzoate. It is ultra-processed.

So obvious questions (to me, anyway): are either benign? Is the lemonade benign (because it’s not a UPF) and the Sprite harmful (because it is)?

Which, if either, is worse: the lemonade because it has more sugar or the Sprite because it’s a UPF? And… what if both the lemonade and the Sprite are sweetened with artificial sweeteners? Fewer calories, no sugar, but an industrial ingredient added instead? More or less benign?

And how would we know? Is it important that we know? This UPF paradigm implies that it’s not. I can’t get there. I’m not ready to give up that reductionist thinking, which has a long and relevant history.

Add sugar and refined grains to a traditional diet, and…?

The concept of refined (aka processed) carbohydrates as being uniquely harmful dates back to the 19th Century. As sugar and white flour spread around the world with the industrial revolution, as I’ve discussed in my books, so apparently did what observers took to calling diseases of civilization—most notably, hypertension, obesity, diabetes mellitus, and coronary heart disease, clustering together both in populations and in patients. And the observers at the time, the ones with their boots on the ground, as the military cliché has it, speculated that this relationship was causal.2

By the 1960s, nutritionists were speculating as to the possibly critical role of sugar in these nutrition/disease transitions, and researchers were beginning to elucidate physiological mechanisms that could explain the connections. By the late 1980s, endocrinologists (Gerald Reaven’s group at Stanford, primarily) were arguing that insulin resistance was a key pathological factor. In their animal studies, at least, the fructose component of sugar seemed to play a critical role (here, for instance).

Nonetheless, when researchers set out to do clinical trials testing various dietary therapies or means of prevention, they ignored these issues almost entirely, ignoring, in essence, all the questions of the day with which I started this post.

Why? My take is that the researchers doing these human trials weren’t interested in elucidating diet-related mechanisms of disease. They wanted to know whether or not the diets prevented or reversed symptoms. They were, after all, mostly physicians doing these trials. They were (and still are) asking the same questions about diets that they would ask about a new drug: Is it safe and effective at preventing heart disease, say, or diabetes, or reducing weight (however temporarily)? Which of two or three diets is safer and more effective? Yes, the diets tested might be based on a hypothesis (saturated fat raises LDL cholesterol and clogs arteries, for instance), but that was as far as their thinking on mechanisms went.

If they got the result they expected, they might comb the literature for mechanistic explanations, but they were fundamentally uninterested in the underlying physiology and competing hypotheses. They were medical doctors, not scientists.

The confounding nature of carbohydrates and calories

That these doctors (and the occasional nutritionist) were interested almost exclusively in diet-efficacy questions explains why they paid so little attention to the methodological issues with their research.

The most relevant in this case stems from the fact that the subjects of these clinical trials, this research, are, well, humans. Counsel them to eat a particular diet, low-calorie, say, or low-fat, with the implication that it will make them leaner and/or healthier, and they will regrettably think for themselves.

The subjects in these trials may follow the advice, but they will also go beyond it. When counseled to cut calories, for instance, they may eat smaller portions, but they’ll also avoid foods entirely that happen to be rich sources of carbohydrates and sugars specifically. Why? Because they know they’re indulgences. Ice cream or cake after dinner? No. Potato chips? No. Coca-Cola? No, or at least not when they can drink Diet Coke instead. Beer? Lite, or not at all. They may think of this as cutting calories, but they’ll be cutting out refined grains and sugars, too.

As a result, the diets followed in virtually all diet trials, and particularly those involving body weight as an outcome, became carbohydrate-restricted diets, even as they might also restrict fat, or saturated fat, or meat, or calories only.

Take, for instance, the famous Oslo Diet-Heart Trial. In 2017, a “Presidential Advisory” published by the American Heart Association identified this trial as one of four “core” trials carried out with sufficient rigor to allow a reliable assessment of the value of replacing saturated fat (SFA) with polyunsaturated fats (PUFA), which in practice meant replacing animal fats with vegetable oils. From these four core trials, all dating to the 1960s, the AHA’s experts concluded that this replacement would reduce heart attack risk by 30 percent.

The Oslo trial was the work of a single investigator, a physician, Paul Leren, who took men who had survived a heart attack and randomly allocated half of them to eat a low-SFA, high PUFA diet. He gave those patients “continuous [dietary] instruction and supervision,” and compared their health over the ensuing couple of years to similar patients who received no counseling and no supervision and ate the standard Norwegian diet. (In short, this was an unblinded, uncontrolled trial without a placebo group, but let’s not quibble with that or the standards used by an AHA presidential advisory group to establish the methodological rigor of a clinical trial.)

As Leren notes in passing in a 1966 monograph, the men counseled to eat the low-SFA/High-PUFA diet also, surprisingly, ate very little sugar: only 50 grams a day, which is 40 pounds a year or less than half the per capita consumption in Norway in that era. They were counseled to replace saturated fats with polyunsaturated fats, and they responded, apparently, by cutting their sugar consumption in half. The trial was then reported as showing a benefit from the fat replacement. But maybe it was the sugar. Neither Leren (nor the AHA) could know.

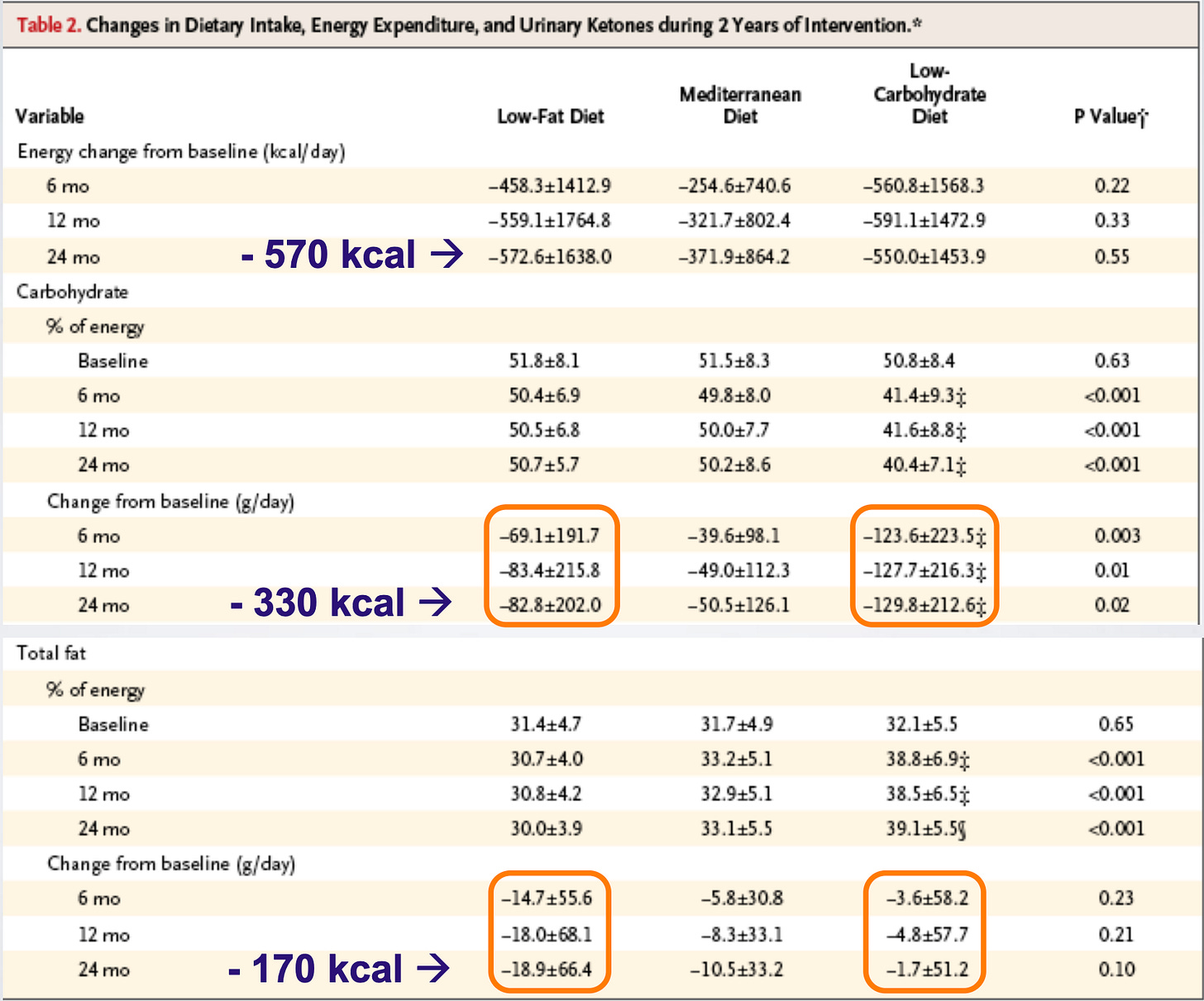

This confounding of calories and carbohydrates was the case even in trials that compared radically different diets—this 2008 trial, for instance, published in the New England Journal of Medicine (since cited, according to Google Scholar, over 3000 times). Participants were randomized to three different diets: low-carb (an Atkins-type diet), a Mediterranean diet, and a Low-fat diet. Now take a look at Table 2 from the paper:

Even the participants randomized to specifically consume a low-fat diet (the first column) restricted carbohydrate calories by almost twice as much as they did fat calories: 330/day after 24 months compared to 170/day.3 In short, the trial compared three carbohydrate-restricted diets—one was also fat-restricted; two were not.

Mediterranean, DASH diets, and “healthy” plant-based diets of all types, as the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine kindly points out, do not just “emphasize the consumption of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes,” and reduce red and processed meat consumption, but they also restrict refined grains and sugars.

When these diets are tested in clinical trials, they’re typically tested against whatever the participants would have typically eaten: if in the U.S., then a standard American diet (SAD), rich in sugar and refined grains. That these diets apparently do better than the SAD is unsurprising, but we can’t know whether their efficacy is due to the emphasis on fruits, whole grains, and legumes, the avoidance of red and processed meat, or the restriction of sugar and refined grains. Even Dean Ornish’s famously very low-fat diet also restricts, if not prohibits, refined grains and added sugars.

When Christopher Gardner, the influential Stanford nutritionist/plant-based-diet advocate, studied a very low-carb diet versus a very low-fat diet in a trial known as DIETFITS, he had the participants restrict high GI carbohydrates and sugars in both diets because he considers these foods unhealthy. Hence, he refers to the diets in his papers as “healthy low-fat (HLF)” and “healthy low-carbohydrate (HLF).” In both cases, healthy is essentially a synonym for the guidance to eat “a variety and quantity of vegetables” and “minimize added sugars and refined grains.”

As I’ve discussed in an earlier post, the epidemiological concept of the healthfulness of a plant-based dietary pattern (a “prudent” diet originally) was largely established by comparing it to a “western” dietary pattern that made sure to include sugar and refined grains in with red and processed meats.

Back to ultraprocessed foods

We can see how this plays out with UPF in a recent Wall Street Journal essay. The author is a science journalist with a new book about the damage screens and UPF are doing to our children’s brains. The title of the essay is “My Family Went Off Ultra-Processed Foods for a Month. The Results Surprised Us.” The author tells us that the family's goal was to avoid all foods that contained preservatives and emulsifiers or any ingredient they couldn’t pronounce. (We’re in Michael Pollan land here, as we are essentially in all UPF discussions from Monteiro’s 2010 article onward.)

This eliminated all foods with artificial flavors and anything with refined flours, including most store-bought crackers, cereals, breads, pretzels, granola bars and the baked goods at our local coffee shops. It meant giving up a bunch of our favorite foods: Cheez-Its, Ritz Crackers, Pirate’s Booty, bagels, pita chips, milk chocolate and flavored sparkling waters…

We decided that without UPFs in the house, we could eat as much as we wanted of the other foods. If we craved a sweet, then we would bake it.

In short, if the advice had been to avoid refined grains and sugars, the only conflict might have been those occasional home-baked sweets and maybe the sparkling waters (if the flavors were artificial).

Not surprisingly, the month of dietary restriction changes their eating habits—the author’s young daughter becomes a much more adventurous eater—and their cravings vanish. But why? Because they were avoiding maltodextrin, soy lecithin, and guar gum, or avoiding refined carbs and sugars? I’m betting the latter (but I’m biased).

We can ask Ashley Gearhardt, a psychologist who studies compulsive eating at the University of Michigan, who serves as the essay’s designated academic authority.

She explains that because ultra-processed snacks, such as crackers, granola bars and gummies (even organic ones), are packed with refined sugars or other carbohydrates, they prompt children to keep snacking.

“After you eat a big hit of crackers or pretzels, two hours later, you’re getting this blood-sugar crash, and you’re craving more snacks that contain refined carbohydrates,” Gearhardt says. “It’s hard to have the hunger for real food if you’ve already eaten so many energy-dense foods throughout the day.”

So why bring in all the ultra-processing baggage—the guar gum and maltodextrin and even the energy density notion—when the same effect/benefits could be accomplished without ambiguity by advising against eating refined grains and sugars? At least then, we’d know what to study.

Back to the latest study: UPFs and reproductive function!

This was an international study in which researchers randomized participants to eat a minimally processed or ultra-processed diet, each for three weeks, and measured factors related to reproductive health, such as sperm quality in men and follicle-stimulating hormone in women. Not surprisingly, the unprocessed diet resulted in better health—metabolic and reproductive—all around.

The annoying question, once again, is why? As the authors reported:

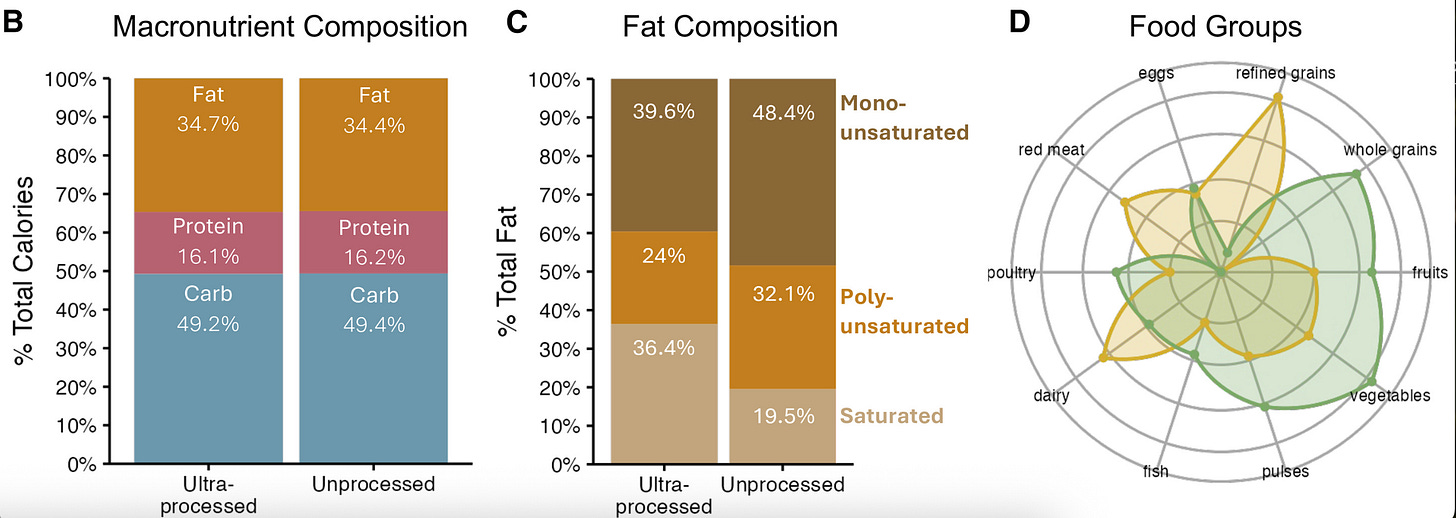

Compared with the unprocessed diet, the ultra-processed diet contained elevated levels of saturated fat, cholesterol, refined grains, added sugars, and dairy products and lower amounts of fiber.

If the photos of the different diets were any indication, the ultra-processed diet included sugary beverages and fruit juices for breakfast, lunch, and snacks, and maybe even dinner (lemonade, yes; but I’m less certain about “elderflower drink”). Not so the minimally processed diet, which included fruit but was otherwise mostly sugar-free.

The paper provided numbers for the macronutrient content of the diets—protein, fats, carbohydrates—and even the fat composition, but not so for refined grains and sugars. In the one figure (D, below right) showing how the diets differed, two categories are conspicuously absent: added sugar and sugary beverages. (This study was funded primarily by the NovoNordisk Foundation and the French Government, but if I were the sugar industry, I might want to get behind this group in the future.)

In short, any of these factors could have been responsible for the relative harms of ultra-processing and, perhaps, sugar or refined grains alone. We have no way to know. If it is sugar and refined grains, shouldn’t we know?

Return of that Bing Crosby Science problem

In a previous post, I discussed the Bing Crosby science problem: accentuate the positive, eliminate the negative. In that post, I was discussing a British UPF trial in which subjects lost weight on the UPF, the exact opposite of what the researchers expected, and they passed over the observation with barely a raised eyebrow.

In a brief article published this week, the New York University nutritionist and food-policy authority Marion Nestle writes that the study confirms that “Ultra-processed diets promote excess consumption.” But, but, but… the subjects lost weight on the diet? Nestle acknowledges the problem but not the refutation to her beliefs that it presents: “Why did the volunteers eat fewer calories than usual on both diets, and significantly fewer on the minimally processed diet?” she asks. “A possible explanation is that they did not like the ‘healthy’ meals and snacks very much.” On this, Nestle and I (mostly) agree. But why did they restrict their intake of the UPFs, a diet that she also says “promote[s] excess consumption?” For that, we get no answer.

The reproductive health trial resulted in a similar conundrum. The subjects were given two versions of each diet: one with “adequate calories” and one with excess. But the difference in body fat and weight reported on the two diets was independent of how much the subjects were given to eat. To their credit, the researchers did discuss it: “This uncoupling between total energy consumed and body weight suggests that total caloric intake is not the sole determinant of body weight gain.”

Yes, it does. Although once again, I wouldn’t want to defend that in a court of science on the basis of this evidence.

Postscript: For those who want a critical and more academic assessment of the ultra-processed food situation, I recommend David Ludwig’s perspective in this week’s New England Journal of Medicine.

Depending on how much juice we get from the lemons.

See the 1975 book, Refined Carbohydrates Food and Disease, and the 1981 book, Western Diseases: Their Emergence and Prevention. Both were edited, with key chapters authored by Denis Burkitt and Hugh Trowell, two former missionary physicians who were convinced the problem with refined carbohydrates was the absence of fiber. This why the subtitle of the 1975 book is “Some Implications of Dietary Fiber.” It’s the legacy of their questionable thinking that carries through to the advice today.

Assuming we can believe the caloric intake numbers which are notoriously unreliable.

Though I am a lowly interested reader (i.e., not a physician, not a scientist, not highly educated in biology, physiology, chemistry or biochemistry, etc.) I am intelligent enough to recognize the problem you elucidate - confounding factors - and I find it preposterous that so many studies have been completed without even attempting to address confounding factors in the design of such studies.

So you're recommending we eat the Mediterranean Diet, right, Gary? Just kidding. To me, the advantage of the keto-carnivore diet is that one can know he's eating that way if he carefully measures and logs his food as he eats it. But I can log all the time, using scales and other accurate measures, and never know if I've followed the Med Diet, because it's UNDEFINED! (Nina described this problem very well months [years?] ago.) It drives me nuts to see so many recommendations for a diet that is so elusive because from the beginning no one knew what it meant and few acknowledge that vagueness. Next is UPF, which seems to have a similar problem. It's not undefined per se, but as you show so well in this article, the definition of UPF is without real meaning. Carnivore's the easiest diet to know you're on. In the Army years ago, they taught me KISS--keep it simple, stupid. So I guess I'll stay with keto-carnivore for now. Thanks!