Bing Crosby Science: Ultraprocessed Food edition.

What do you do when the latest clinical trial contradicts the core assumption of UPF science? How about accentuate the positive and eliminate the negative?

With ultra-processed foods (UPFs) in the news almost daily, they’ll also be the subject of today’s quiz. Question 1 is multiple choice.

If one of the few facts we can trust about nutrition science, according to an essay published on Thursday in The New York Times, is that “a diet high in ultraprocessed foods results in eating more, leading to weight gain,” then what should we make of a clinical trial reported in the Times just three days earlier showing that people fed a “healthy” ultraprocessed diet apparently ate less and lost weight?

A) Conclude that our thinking about the harms of ultra-processing may need some serious revision.

B) Conclude that neither “healthy” nor “ultra-processed” mean what we think they mean.

C) Ignore the elephant in the living room and focus on the furniture instead.

D) Skip straight to the more instinctive (if mildly obscene) reaction: wtf!?

If, as implied by question 1, UPFs can be either healthy or unhealthy, fattening or not, in ways that have little to do with the ultra-processing, can we find a way to regulate these foods that doesn’t do at least as much harm as good?

Short answers: 1), A (or maybe D), but for nutrition reporters, apparently C. And 2), maybe yes, and it’s a legalistic sleight of hand that starts with the 21st Century concept of ultra-processing and acts on it via the 20th Century thinking of the dangers of refined carbohydrates and sugars.1 I’m a fan. Read on.

FDA and USDA ask for UPF clarity and the CDC reports numbers

Let’s start with the uncomplicated news on UPFs.

With the MAHA initiative targeting UPFs as a significant problem with the American diet, the FDA and USDA released a request for information on July 25th “to help develop a uniform definition of ultra-processed foods (UPF or UPFs) for human food products in the U.S. food supply.”

A uniform UPF definition, developed as part of a joint effort by federal agencies, would allow for consistency in research and policy to pave the way for addressing health concerns associated with the consumption of UPFs.

A week later, the CDC reported that if UPFs do cause health concerns, Americans are in deep trouble. As a population, it seems, we get over half our calories from these foods, with “[s]andwiches (including burgers), sweet bakery products, savory snacks, and sweetened beverages” topping the lists.

For those unfamiliar with the concept, UPFs are defined as those foods, quoting the Times, that are “made via industrial methods or with ingredients, like high-fructose corn syrup or hydrogenated oils, that you wouldn’t typically find in home kitchens.”

From our perspective, the critical point about UPFs is that any deleterious health effects they might cause are assumed to be independent of their macronutrient content, or how those macronutrients specifically are refined. As a Nature Medicine article (which I’ll get to shortly, as it’s the the wtf!? trial) recently described this thinking, “evidence suggests that the associations between UPF and adverse health outcomes are not explained by macronutrient or food group guidance within dietary recommendations.”

In short, nutritionists are now willing to believe that a “sweetened beverage” or “sweet bakery product” may have “adverse health outcomes” not because they’re loaded, say, with sugar (sweet!), but because they’re ultra-processed and made with ingredients that you’re unlikely to find in your kitchen (high-fructose corn syrup!). And a “savory snack”—a potato chip, for instance—may have an adverse health outcome for the same reason. Hence, a particular food can be healthy if you cook it in your kitchen, but will cause chronic disease if made, say, by General Mills.

By embracing this thinking, public health authorities, MAHA, and an alarming number of nutritionists now seem to believe that future scientific progress will come from studying these UPFs as a category—comparing UPF diets to minimally processed food (MPF) diets—and public health breakthroughs will come from targeting UPFs in the food supply as a monolithic category.2

“For nutritional scientists, this focus,” as a recent Nature Medicine news article on UPFs explained, “challenged decades of dogma that analyzed foods based on specific qualities such as protein, fat, sugar and salt content.”

That Nature Medicine article is not uncritical. It quotes influential nutritionists questioning whether the UPF concept adds anything of benefit to public health guidance—”many of the nutritional concerns about UPFs,” it says, “are captured in existing dietary guidelines.” And it points out that the evidence supporting the UPF concept is what lawyers would consider circumstantial: mostly observational (associations not causality) with a few trials that “only capture a short time frame, all of which hinders what we can truly say about the healthiness—or lack thereof—of UPFs.“

The article then observed that the tipping point in UPF research was a 2019 NIH trial led by Kevin Hall, who has since left the agency (but is no less influential). It was this NIH trial that locked in what is now the core assumption of the field: UPFs do their harm by making people eat too much. Its title was unambiguous: “Ultra-Processed Diets Cause Excess Calorie Intake and Weight Gain.”

Quoting Nature Medicine again (with my emphasis added):

At the National Institutes of Health (NIH), researcher Kevin Hall undertook the first controlled study of UPFs, expecting to find that they were equivalent to other foods. In fact, he found the exact opposite. Ten participants spent four weeks living at the NIH. For the first two weeks, they each ate either an all-UPF diet or a minimally processed diet; they then ate the other diet for the last two weeks. Hall found that, on the UPF diet, participants ate an extra 500 kcal per day and gained an average of 0.9 kg over two weeks. This 2019 study was a lightning rod for UPF researchers, since it was the first concrete evidence that these foods were somehow different.

I wouldn’t have been so quick to use words like “concrete” or even “first” in this context, but I’m not writing for Nature. The point is that the NIH trial has been treated with such reverence that it’s rarely mentioned without the word “landmark” preceding it as the requisite adjective.3 And it’s the NIH trial that led directly to statements like this one from a recent NPR article, placing the conventional thinking on UPFs into a convenient nutshell:

There's a growing consensus among scientists that many ultra-processed foods trigger people to overeat. "Ultra-processed foods are engineered for people to over-consume them," says psychiatrist Agnes Ayton at the Royal College of Psychiatrists in London.

These foods derail two critical aspects of our eating behaviors, Ayton says. They can prompt people to start eating even when they're not hungry, and they can keep us eating even when we're full.

The catch, as I’ve discussed in several previous posts, was that the NIH study was also fiercely criticized. (Harvard’s Walter Willett, for instance, among the most influential nutritionists in the world, has called it “worse than meaningless.”) Its most conspicuous shortcoming: the participants in the trial were fed the diets for only 2 weeks: i.e., a very “short time frame.”

This left Hall and his NIH colleagues strongly implying that changes in human behavior (how much we eat) that manifest over the course of two weeks in a clinical trial can be safely extrapolated to what happens in the real world over the years to decades it takes obesity to develop.

I find that hard to imagine4, but the nutrition research community certainly doesn’t, nor do public health authorities. Even the MAHA report cited the NIH trial repeatedly as damning evidence against UPFs and their eating-too-much role in the obesity epidemic.

So this raises the obvious question: what would happen if researchers attempted to replicate the landmark NIH study but do so with a trial lasting longer than 2-weeks?

Uh-oh! Maybe ultra-processing does not make people overeat?

The trial published this week in Nature Medicine did just that. Like the NIH trial, it was a “[r]andomized Controlled Trial of Ad Libitum Food Intake.” Ad libitum means the participants could eat as much as they want. They were neither encouraged nor expected to lose weight.

Like the NIH trial, the new trial compared a UPF to an MPF diet, and it was a feeding trial: the participants were provided the food they were expected to eat and more than enough of it.

Unlike the NIH trial, it was not an in-patient study with participants housed in a metabolic ward. Rather they lived at home in this new trial, and went about their lives.

Like the NIH trial, the participants ate both diets in random order. Unlike the NIH trial, they did so for eight weeks per diet, not two.5

The researchers hailed mostly from University College London. Kevin Hall was a co-author, as was Chris van Tulleken, author of the bestselling and widely-praised Ultraprocessed People. Like Hall, the UCL researchers went into their trial with expectations of what they would find. They assumed the UPF diet would lead to weight gain and the MPF diet would not, because that’s what Hall had observed.

Like Hall, their expectations didn’t pan out.

Unlike the NIH trial, the UCL trial attempted to make both the MPF and UPF diet healthy, at least by the standards of current UK nutritional thinking. They designed both diets to satisfy the criteria of the Eatwell Guide, which is the UK version of the USDA Dietary Guidelines. This meant that the foods would be generally lower in fat and saturated fat, and would also limit sugar. I’m going to assume that sugary beverages (even fruit juices and smoothies) were discouraged on both diets. Beer, too.

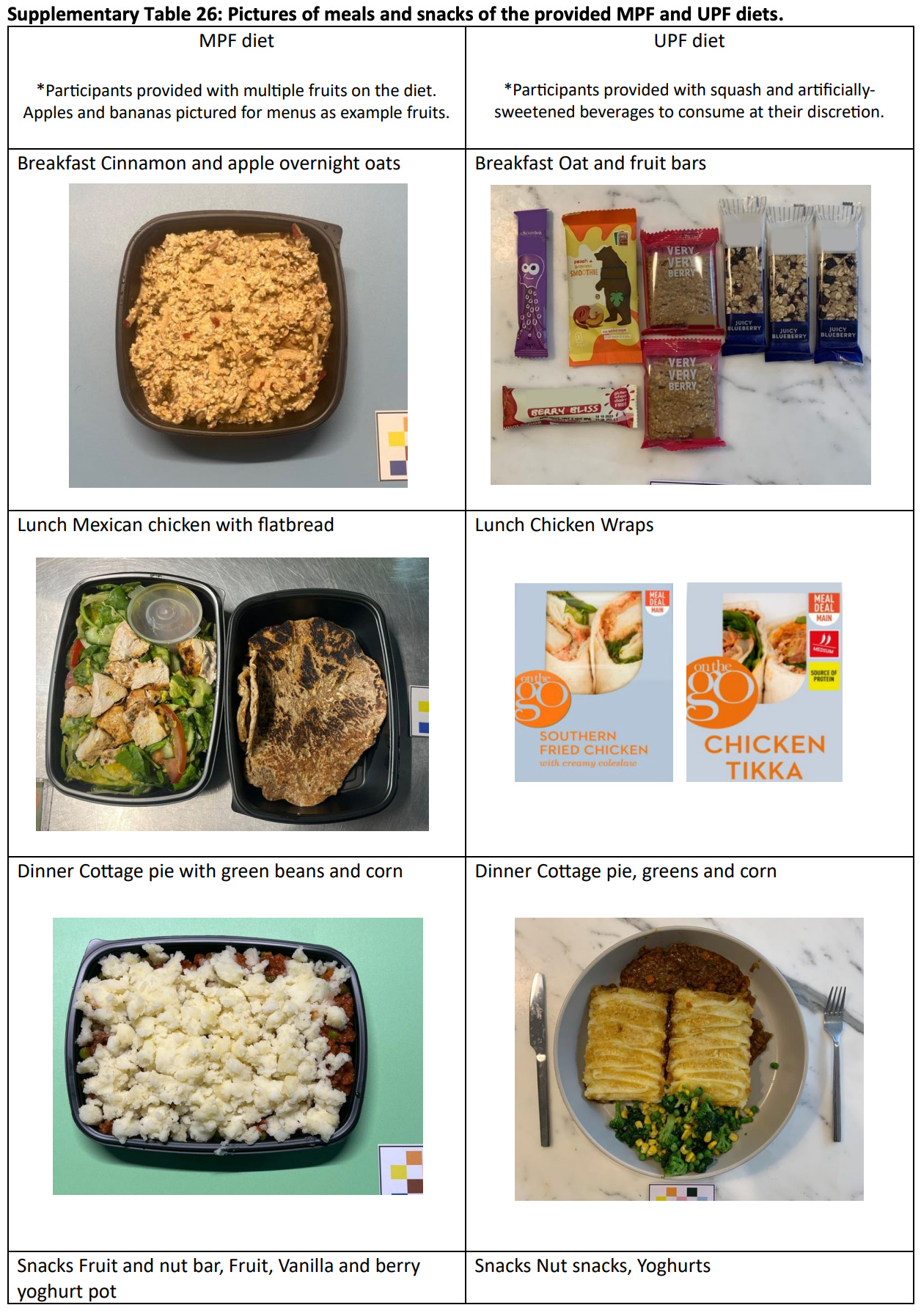

Here’s an example of a day’s menu, MPFs on the left, UPFs on the right:

So what did they find?

The participants lost weight on both diets. That’s the important finding, because UPFs are supposed to make us gain weight—i.e., all that “derailing of critical aspects of our eating behavior.” Clearly, though, this isn’t necessarily true. If folks are actually paying attention, and maybe if they want to lose weight—one reason why people volunteer for these trials—they can do so whether or not the food is ultra-processed. At least for 8 weeks.

Now in my universe this is a profound observation (assuming it’s right) because it contradicts the conventional wisdom in the field. It contradicts the interpretation of Hall’s “landmark” NIH trial, as well as a one-week Japanese trial that nutritionists consider confirmation.6 As such, it is what the Enrico Fermi, the legendary physicist, might have called a discovery, rather than a measurement:

There are two possible outcomes: if the result confirms the hypothesis, then you've made a measurement. If the result is contrary to the hypothesis, then you've made a discovery.7

But that’s not how it was treated. As it turns out, the participants lost about 2 % of their body weight over 8 weeks on the MPF and only 1 % on the UPF. (Although whether this difference was statistically meaningful depended on the analysis used.8)

Here’s how the paper discussed this discordance with expectations (my emphasis):

In contrast with our hypothesis given the body of observational evidence linking UPF with weight gain, the UPF diet following UK dietary guidance resulted in weight loss. However, weight loss on the MPF diet was significantly greater than on the UPF diet. Our study therefore confirms and builds upon previous findings, showing significant differences in weight change between matched UPF and MPF/non-UPF diets, within the context of existing healthy dietary guidance.

The summary abstract pointed only to the “greater weight loss on MPF than UPF diets” as the finding of importance. Not the discovery, for lack of a better word, that UPF diets can induce weight loss.

The media followed along. The Times headline was “Avoiding Ultraprocessed Foods Might Double Weight Loss.” And the subhead: “In a new trial, people consumed more calories and had more cravings when they ate ultraprocessed foods.” “Eating ultra-processed foods could make it harder to lose weight,” hailed the Guardian. Even the journal Nature covered the trial, with an article headlined “Home cooking and minimally processed foods best for weight loss, study finds.”

While the Times article nodded to the fact that the study results contradicted the one assumption about UPFs that was considered iron clad—giving Kevin Hall credit for the observation—they passed over it in a single word (my emphasis):

It was somewhat surprising — and encouraging — that people lost weight on the ultraprocessed diet, said Kevin Hall, a nutrition scientist and a coauthor of the study. This was likely because the study’s ultraprocessed diet was more nutritious than the typical diets of the participants, he said. But participants still lost more weight on the minimally processed diet — a finding that aligns with those of previous studies.

As for me, I was neither surprised by the coverage, nor encouraged.

The essence of bad science

If one characteristic defines all bad science, it’s the tendency to downplay evidence that challenges core assumptions and attend only to the evidence that agrees with them. Francis Bacon pointed this out as an inherent flaw in human reasoning when he pioneered the scientific method 400 years ago, and it’s not going away.

When I first investigated nutrition research for the journal Science back in 1998 (“The (Political) Science of Salt),” I quoted Graham Watt of the University of Glasgow describing this knee-jerk selection bias in a way that I found particularly memorable. He called it the “Bing Crosby approach to epidemiological reasoning”—i.e., “accentuate the positive, eliminate the negative.”

The Bing Crosby approach, as I wrote then, “allows researchers to find the effect they're looking for in a swamp of contradictory data but does little to establish whether it is real.” What I implied but should have made explicit is that it allows researchers to hold fast to their preconceptions, whether or not they’re right.

So does the ultraprocessing of food make us overeat? Is that why we get fat, as individuals or as societies?

Not according to this latest clinical trial, arguably the best we have. But you’d never know that from reading the news accounts, and you’d have to read the study itself damn closely to realize that while maybe it “builds and confirms” a secondary proposition of the UPF science—that people tend may consume more calories from UPFs than MPFs—it directly challenges the core assumption of the field.

The media and the research community seem content to accentuate the positive in this business, but the very concept of UPFs depends on the notion that industrial processing is the problem, not the processing of specific macronutrients. As such, it may be one of the many conceptions in science that work to lead researchers further from the truth, not toward it. The UPF conception may do more harm than good.

After all, if we can lose weight on a UPF diet without trying all that hard, maybe it’s those other factors that make a diet “more [or less] nutritious,” as Hall suggested to the Times—sugar, perhaps, or processed carbohydrates specifically?—that we should be worrying about.

A solution?

This brings us to the latest UPF-related news. On Wednesday, David Kessler, a former FDA commissioner and medical school dean (at Yale and UCSF), submitted a citizen petition to the FDA suggesting a work-around to the UPF quandary. The headline of the Times article on Kessler’s petition suggested he was backing the MAHA approach to regulating UPFs, but he was doing it by going after the refined carbohydrates and sugars they contained (i.e., 20th Century science). Here’s the NYT (with my emphasis):

In a citizen petition filed late Wednesday and shared with The New York Times, Dr. David Kessler, who held an advisory role in the Biden administration, argued that the agency he ran more than 30 years ago has the authority and the scientific evidence to declare that some of the core ingredients in ultraprocessed foods are no longer “generally recognized as safe.”

That includes sweeteners like high-fructose corn syrup and certain refined flours and starches like maltodextrin, dextrose and corn solids, which are used by the food industry but not in home cooking. A citizen petition is a formal request to the F.D.A.; the agency is obligated to respond in 180 days…

His petition relies on the argument that modern scientific research has found a close link between consumption of refined carbohydrates — sweeteners, flours and starches — and weight gain, heart and kidney diseases, certain cancers, and other serious health conditions.

He asserts that body of evidence means the F.D.A. can no longer allow such ingredients to be “generally recognized as safe,” or G.R.A.S., which is a designation that allows companies to circumvent a cumbersome and lengthy approval process for food additives.

…By going after core components of ultraprocessed foods, like refined sugars and starches, the F.D.A. can effectively regulate them, [Kessler] said….

The petition solves the problem that I worry about, the lack of definitive evidence demonstrating that refined carbohydrates and sugars (whether sucrose or HFCS) are, indeed, harmful, by relying on the FDAs definition of whether or not a food is “generally recognized” as safe. These foods no longer are, even if the reason they’re not is still open to question, which may be a problem.

Kessler, for instance, thinks the problem with refined carbohydrates and sugars is that (quoting the Times, they’re “`conducive to rapid eating, rapid digestion,’ and thus lure people into overeating.” For sugar, that’s a variation on the empty calorie thinking that has dominated the nutrition world for half a century.

If the food industry can challenge Kessler’s proposed regulatory approach on the basis that we can’t regulate against foods because we like them and so eat too much, I think the industry will win. (See this Times op-ed I wrote in 2017.) But if it can’t, as Kessler believes (and I defer to his expertise here), then this is a way to solve the problem of refined carbohydrates and sugars in modern diets in the absence of the lengthy, expensive and perhaps impractical clinical trials that could provide definitive evidence.

It’s a clever approach, perhaps a solution, to a very important problem.

Another way to think of this UPF conception is as a new take on what nutritionists have been advocating, implicitly or explicitly, for decades: cook our own meals, avoid fast food, and eat no foods sold in the interior aisles of the supermarket or by any store that even vaguely resembles a 7-Eleven.

The New Yorker, for instance, also called it “hugely influential and… widely recognized as the most rigorous examination of the subject so far.”

Considering, after all, that the outcome of overeating these UPFs—i.e., the adverse health effect—is the burdensome chronic disorder that most of us think obesity to be.

Unlike the NIH trial, the participants had a four-week wash-out period between diets, which was a vest improvement over none at all, but still might not have been sufficient to avoid what are called carry-over effects (as I discussed here).

The title of that study, as with the NIH trial, was unambiguous (with my italics): “Ultra-processed foods cause weight gain and increased energy intake…”

H/t P.J. Ungar for reminding me of Fermi’s quote.

The greater percentage weight loss on the MPF diet vs the UPF diet depended on how the results were analyzed. One analysis is called a per protocol analysis, which is based only on the participants who finished the trial. By this analysis, the weight loss difference between the two diets fails to be statistically significant. The paper itself mentions that this analysis was done and that the results are presented in two tables (20 and 21) of the 54 pages of supplementary material, but not what those results were. As it turned out 12 of the original 55 participants dropped-out of the trial (every last one of them after being assigned to the MPF diet, which is head-scratching). An Intention-to-Treat or ITT analysis accounts for drop-outs and noncompliance and this is what the researchers said in their protocol paper they would use for the primary endpoint. By this ITT analysis, the percent weight loss between the two diets was significantly different and this is what the paper reported. If ChatGPT is to be believed, “Most high-quality trials report both [per protocol and ITT], allowing a more nuanced understanding of both effectiveness and efficacy.” I’m not sure burying one of the analyses in the supplemental material constitutes reporting both, but… I’m just a journalist.

Viewing those images does nothing to reduce stereotypes about British food. I’d lose weight if you fed me that slop. Heck, the only way I’d eat that slop is if I were in prison.

Also, it all seems more processed than what I eat most of the time. Except for my daily protein shake laced with creatine.

Great article as always, Gary. As to your last line "...in the absence of the lengthy, expensive and perhaps impractical clinical trials that could provide definitive evidence," I as one loyal subscriber am, like you (I am guessing) gosh darn tired of the excuses from the bloated government agencies for why they don't actually do the necessary work. "Expensive?" YGBFKM! Ask the President for some of the impounded money saved from the dismantling of USAID, for crying out loud. Or divert some of the money saved from the departure of 25% of the IRS workforce. "Impractical?" I simply don't accept that assertion. It has never stopped agencies from conducting their confirmation-biased studies in the past. How about asking Mr. Kennedy, et al, - team MAHA - to be bold and brave here, and, to commit to a big worthy project, impracticalities and all?

It's well past time we stop settling for government agencies making rules based upon weak/nonexistent evidence. It's not too much to ask.

Thanks again for the enlightening discourse.