Are Ultra-Processed Foods the Problem?

With all the interest in the dangers and addictive nature of ultra-processed foods, can we start, please, with the right questions and the right experiment?

On one issue, at least, we're all (mostly) in agreement. If we're going to fix the health of Americans, beginning with America's children—per the MAHA report released in May—we'd better start with diet, and starting with diet starts with the problem of ultra-processed foods (UPFs).

Why UPFs? The argument is pretty simple. The past sixty years has seen epidemic increases in chronic diseases—obesity and diabetes, most prominently—and this increase associates with an ever-growing prevalence of UPFs in the American diet. Here's the MAHA report on the gist of it all:

Most American children's diets are dominated by ultra-processed foods (UPFs) high in added sugars, chemical additives, and saturated fats, while lacking sufficient intakes of fruits and vegetables…. The excessive consumption of UPFs has led to a depletion of essential micronutrients and dietary fiber, while increasing the consumption of sugars and carbohydrates, which negatively affects overall health.

Nearly 70% of an American child's calories today comes from ultra-processed foods (increased from zero 100 years ago)1, many of which are designed to override satiety mechanisms and increase caloric intake.

So what's the mechanism? The MAHA report says "nutrient depletion, increased caloric intake, and exposure to harmful additives." The increased caloric intake, of course, implies these UPFs entice us to eat too much: i.e., they're the reason why we (or America's children) get fat.2 "Compelling experimental research further underscores these issues," according to the MAHA report.

A 2019 study published in Cell confined 20 adults to an NIH facility, where participants consumed unlimited UPFs for two weeks, followed by two weeks of unlimited unprocessed foods. Despite having identical caloric access, participants consumed roughly 500 fewer calories per day and lost 2 pounds on the unprocessed diet, while they gained 2 pounds on the ultra-processed diet.

That “compelling” research is the "landmark" study by former NIH researcher Kevin Hall I discussed in my last posts (here and here). Those focused on two critical design flaws that were built into Hall's experiment making it impossible to reliably interpret.

This post discusses what experiment should have been done. If we want to solve the UPF problem—assuming for the moment that there is a UPF problem other than perhaps the concept of UPF itself—it might help to start with the right experiment.

UPFs take the world by storm (in more ways than one)

Among the remarkable aspects of the UPF story is how quickly this concept was accepted as a supposedly meaningful contribution to the science of diet and chronic disease. Nutrition researchers bought into a scientific-sounding repackaging of the concepts of junk food with lightning speed (by science standards) and then began designing studies to establish the mechanism by which these UPFs might damage our health. What they didn't do is design studies to question the UPF concept itself.

Here's an easy way to think about the issue: Assume for the moment that UPF is, as I believe, just a synonym for junk food and fast food. Would we bother designing studies that try to identify mechanisms by which all junk/fast foods en masse might be ruining our health: candy bars, sodas, chips, French fries, McDonald's hamburgers, etc., all harmful in the same way because they're all junk? Would we assume that other foods with similar macronutrient compositions are not harmful because, well, they're not junk foods? Mom's apple pie is benign but McDonald's apple pie isn't?

UPFs, as I discussed in this January post, are defined not by their macronutrient content and the processing of particular macronutrients (carbohydrates and fats specifically)—described by a researcher in the New Yorker dismissively as "a very twentieth-century way of thinking"—but the number of ingredients, the chemical nature of the ingredients, whether the ingredients were added in a factory or a fast food restaurant or a home. The implication is that whether a food was prepared with love by a member of our family or to make a profit by an industrial concern is a determining factor in whether it's good for us.

I don't buy it, but I could very obviously be wrong. So before we get to the question of how UPFs might inflict their damage—assuming one UPF is very much like any other UPF—how about we ask a different question entirely: does this UPF concept tell us anything meaningful about the relationship between diet and chronic disease?

We can see why it might not from a 2023 Wall Street Journal article headlined "Is That Food Ultra-Processed? How to Tell." Here's the breakfast course in the learning experience: two Quaker cereals, both oatmeal.

“The Quaker brand,” explains the WSJ, “has oat products that nutrition researchers would consider ultra-processed, right, and ones that aren’t ultra-processed, left.”

The old fashioned Quaker oats has one ingredient: whole grain rolled oats. It’s presumably healthy. Not so the instant oatmeal:

What makes the instant oatmeal ultra-processed—i.e., why we should avoid it if we quite literally know what’s good for us—is the number of ingredients and specific ingredients, which the WSJ identifies with the red rectangles: “whey protein concentrate,” “whey protein isolate,” “soy lecithin, natural flavor”.

But here's an obvious question: What about the sugar? That comes second on the ingredient list, meaning it constitutes the second greatest percentage by weight. In fact, 20% of the calories in the instant oatmeal come from sugar.

If the ingredients were only sugar and whole grain oats, this would not be an ultra-processed food. Would that make it benign, as the UPF classification implies? Of the 10 ingredients listed in the instant oatmeal, should we really worry about the eight that come after the sugar? Or should we worry about the sugar? If we were to eat more of this instant oat meal than the old-fashioned variety, would it be because of the sugar or because of the 8 ingredients that combine to make it a UPF?

If we make ourselves a bowl of old-fashioned Quaker Oats and sprinkle three teaspoons of sugar on it (12 grams), that would still be categorized as a minimally processed food. Healthy or not?

As soon as we start thinking in terms of UPFs—21st Century nutritional thinking, for better or worse—we lose all the distinctions regarding macronutrients.3 As soon as the nutritionists came to think of their research as trying to determine what it is about UPFs that might make them seemingly unhealthy, they skipped over the stage in which they actually test the validity of the UPF concept itself.

But maybe it's not the UP-ness of a food that makes it unhealthy? Maybe it is the 20th Century thinking of macronutrients, sugar, fat, glycemic index, etc. Maybe all the rest—the whey proteins, lecithins and flavorings and dyes—is window dressing. Even if these additives are harmful, maybe they're very minor insults in this context of much greater harms.

How do we find out? Not by the kind of research that Hall did and MAHA cited so prominently.

What makes a diet trial compelling research?

The reason why nutritionists and policy wonks use words like “compelling” to describe Hall's study is because he housed his subjects in a metabolic ward and could control what they ate. Lack of adherence to dietary counseling is a problem with many trials studying the relationship between diet and health, so this solved that problem.

But that problem is not, by any means, the only problem with these studies. Indeed, when the medical and public health authorities remind us (and maybe themselves) that “randomized controlled trials” are the gold standard of evidence in medicine, this is not even the kind of control that they mean.

In the context of an RCT, controlled refers to the use of a control group and, critically, the use of a placebo so that the subjects are unaware (blinded) to whether they are getting the active intervention or not. The placebo controls for ways in which that awareness might effect how they respond (consciously or unconsciously).

Another critical issue with virtually all nutrition trials is that it's effectively impossible to blind the participants to what they're eating. (Virtually, as I’ll discuss, is the operative word here.) Low-fat diets don't look or taste like high-fat diets. Mostly-plant diets don't look or taste like mostly-animal diets.

But now let's take a look at the foods that Hall and his colleagues fed their subjects. Their goal, remember, was to establish whether people eat more of ultraprocessed foods than unprocessed. After all, the UPF supposedly make them fatter. Here's a typical example, an ultra-processed lunch on the left and an unprocessed lunch on the right:4

Now frankly, I'm a fan of salmon and full fat unsweetened yogurt (green beans, not so much), but I can imagine why the subjects in the NIH experiment might not be. So if they ate less of the unprocessed menu, maybe it was because they liked it less. One of my kids likes salmon and one doesn't. They both like hamburgers and French fries (although, I admit, they like fast food burgers better than mine).

Maybe the salmon, green beans and unsweetened yogurt signaled “healthy diet” to the subjects, and that kind of dietary virtue-signaling goes along with the message to eat in moderation. Maybe the subjects got the hamburgers and French fries and thought, "screw it! I'm just going to eat as much as I want. I'll be out of here in two weeks anyway." We can probably imagine dozens of such possibilities, all of which would have little to do with the UP-ness of the UPFs. All of these would be meaningless in a real world setting or once the subjects realized they were getting fatter and assumed that eating less was a good idea.

The right experiment: Testing the effect of ultraprocessing itself

So why not blind for the UPF-ness of the foods? Here's where that virtually comes in. This is one context in which subjects can be mostly blinded to whether they’re getting minimally processed or ultraprocessed foods. Put simply, we can actually test whether or not all the various factors that go into defining a food as a UPF (and so harmful, in theory) is meaningful.5

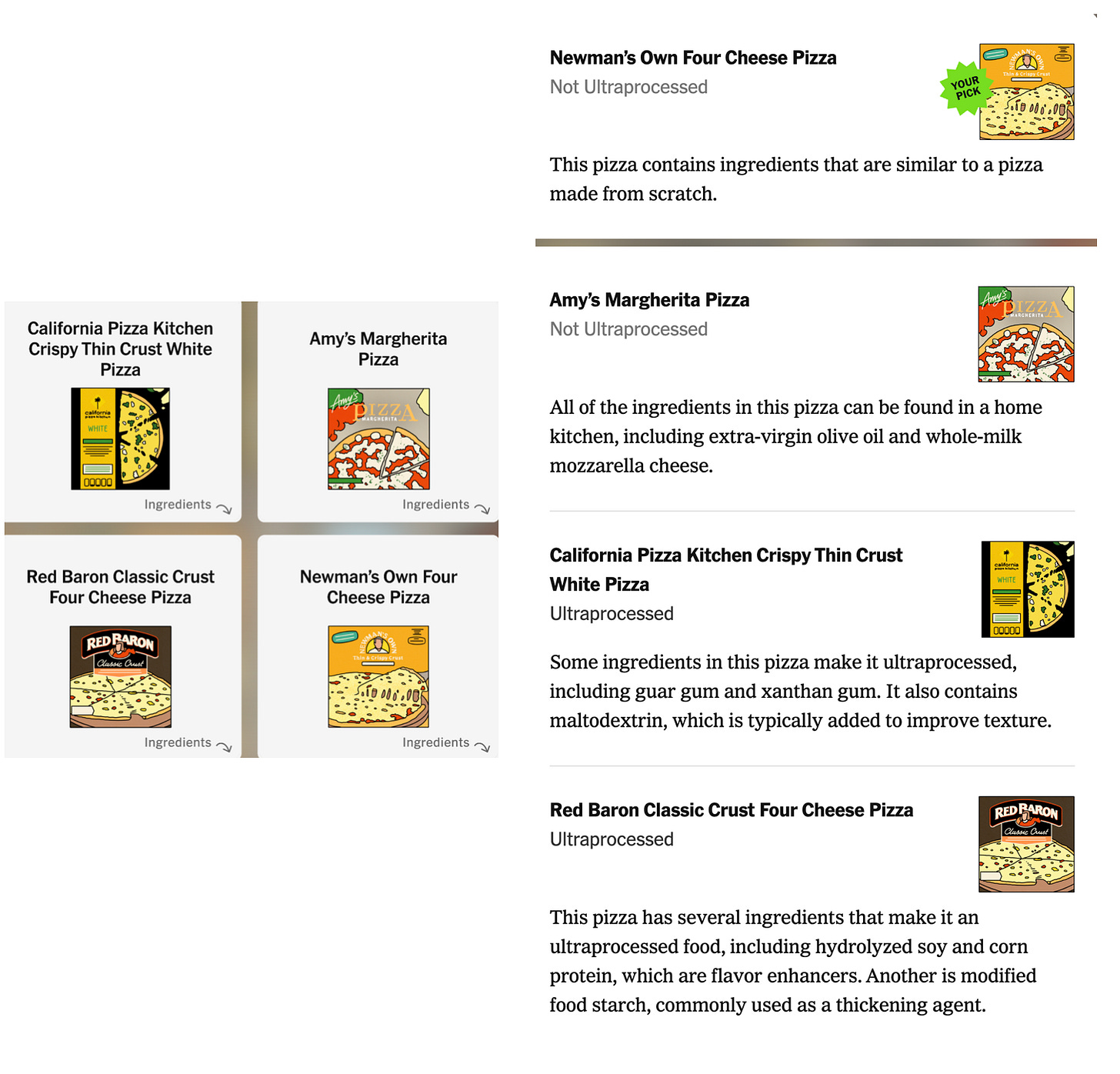

The New York Times did the hard work for us in an article published last January, the NYT version of the WSJ learning experience, : "Are the Foods in Your Cart Ultraprocessed?" It's a quiz in which we're given a choice of four items to buy, some UPFs, some not. The categories: drinks, cereals, frozen pizzas, ice cream, vegan staples, yogurts, and sweet snacks. The Times didn't bother controlling for calories or macronutrients, but it would not be hard to do.

Here are the pizzas, for instance:

Here are the ice creams:

The point should be clear. We can purchase foods that are UPFs or not—pizzas for lunch, cereals for breakfast, ice creams for dessert, snacks, etc. We can even match them for macronutrient content: UPF peanut butters (Jif, with fully hydrogenated vegetable oils, mono and diglycerides) and non-UPF peanut butters (Smuckers, with only peanuts and salt); UPF breads and non-UPF breads; even jams and jellies, UPF or minimally processed.

If the researchers are feeling industrious they can prepare the non-UP foods in a home kitchen and purchase the UPFs at the local Stop & Shop. The critical requirement is that the subjects be unable to determine which they're getting (other than whatever differences in taste are unavoidable because of the UPF ingredients). Now, if the subjects consume more of the UPFs than the non-UPFs, we can consider blaming the ultra-processing itself, not the simple fact that they didn't like salmon and green beans or preferred sugar-sweetened yogurt to unsweetened.

This experiment would tell us whether the UPF classification scheme tells us anything meaningful about the healthfulness of the foods. Thanks to the nutritionists embracing this UPF concept so uncritically, that's now become step one in addressing the chronic disease problem.

There's a catch, of course. The experiment would have to run for a lot longer than two weeks to detect meaningful differences in health status. But that's the case anyway, as discussed in the previous posts.

So if we think UPFs are making people fat and sick because of the industrial ingredients and the number of ingredients, how about we do the kinds of experiments that can establish if that is true. Then we can move on to maybe learn something meaningful.

Postscript: As I was writing this, I noticed that the latest episode of the Maintenance Phase podcast is on the UPF issue. Michael Hobbes and Aubrey Gordon discuss the Hall study at great length. I have mixed feelings about the podcast (and I suspect Hobbes and Gordon have, at best, mixed feelings about my work), but Hobbes and Gordon do a delightful job in this episode critiquing the NIH research. I recommend it.

That the MAHA report says zero in 1920 is a mind-boggling, unless they want us to believe that soft drinks (Coca Cola! Pepsi!) chocolate bars (by 1920: Tootsie Rolls, Hershey’s Milk Chocolate bar, Hershey’s Kisses, Toblerone, the Heath bar…) and, of course, breakfast cereals (courtesy of Kellogg’s and Post) were not UPFs.

This is the implication of this week’s UPF-related article in the Wall Street Journal suggesting that soft UPFs are more harmful than crunchy UPFs (I kid you not) because we eat them faster and so are more likely to overeat them.

I’m going to bet that the oatmeal in the UPF version also has a markedly higher glycemic index than the old-fashioned oatmeal. We lose that distinction, as well. If the processing of the oats makes a difference—20th century thinking—we no longer care.

If you worry that I’ve chosen a particularly extreme example, you can see all the various meals in the supplementary material here.

A year ago March, Nina Teicholz suggested much the same for a study about UPF-addiction in her Unsettled Science substack.

Seems to me that the UPF concept is a great gift to the sugar industry. That's what Hall's real genius is-- coming up with an alternative "scientific" paradigm that simultaneous exonerates the food industry while also "blaming" it and opening up new "research" revenue streams, and new product and marketing opportunities for the likes of Unilever. Coming up -- "Ben and Jerry's Healthy Simple Ice cream -- no UPF ingredients! No guar gum! Just cream, sugar and eggs at twice the price!"

"Most American children's diets are dominated by ultra-processed foods (UPFs) high in added sugars, chemical additives, and saturated fats, while lacking sufficient intakes of fruits and vegetables."

What about protein and good saturated fat????? Why is that NEVER mentioned?????

Gary, I'm not sure if it was you or Dr. Eades or someone else who wrote once about insulin levels increasing as food gets more processed. It was something like they had a person eat a whole apple and then measured insulin (I don't think it was blood glucose they measured). After a period (a day?), they had the same person eat an equivalent apple that was cut into smaller pieces, but having the same amount of calories. The insulin level was higher after the cut-up apple than with the whole apple. After another period, they had the same person eat an amount of unsweetened applesauce equal to the calories in the whole apple. The insulin level went even higher. I think the last test was having the person drink unsweetened apple juice with equivalent calories. Insulin was the highest yet. Anyway, something like that. Does that ring a bell?